Technology

This is a most excellent place for technology news and articles.

Our Rules

- Follow the lemmy.world rules.

- Only tech related content.

- Be excellent to each other!

- Mod approved content bots can post up to 10 articles per day.

- Threads asking for personal tech support may be deleted.

- Politics threads may be removed.

- No memes allowed as posts, OK to post as comments.

- Only approved bots from the list below, this includes using AI responses and summaries. To ask if your bot can be added please contact a mod.

- Check for duplicates before posting, duplicates may be removed

- Accounts 7 days and younger will have their posts automatically removed.

Approved Bots

Considering the two studies which claim that no effect was observed, I believe the original authors observed the effect but they don't fully understand the origin.

The original paper is so naively unprofessional in some places that it is really hard for me to think it is not genuine.

My first reaction to this comment was "yeah, but the quality of the paper has nothing to do with whether or not it is true".

On second thought, I'm not sure about that. I mean, a low quality paper isn't a good signal, but on the other hand, the presentation of an argument doesn't change whether or not it's true.

At least we know there are other labs trying to replicate, we already have rumors of some replications.

My point was that if they would be trying to forge the results, they would likely write a better paper. Like, I have never seen nor would I use a phrase like:

Humankind has long learned that the properties of matter stem from its structure.

or

It is the superconductor with the same color as typical superconductors.

in the results section. It just reads like a student report.

So while it does not prove whether it is correct or not, it, at least in my understanding, indicates that it is genuine. The explanation might be off, the important step of the synthesis might include adding a teaspoon of luck, but the observations/measurements part I believe. Which is what I meant by the comment.

You're kind of discounting the concept of credibility. People make all sorts of wild claims—far too many to actually test them—so it's necessary to weed out claims that aren't credible by looking at things like how well the claims are presented. A new theory in physics will be ignored if it's written in crayon in scraps of trash, as it should be.

Obviously the recent claims about superconductivity are a lot more credible than that, and a bunch of researchers around the world have decided their claims are worth testing, but there's nothing wrong with tempering your optimism in response to a paper that seems a bit dodgy. It's not unreasonable to suspect that researchers who can't get their shit together enough to release a paper without drama might also have trouble getting their shit together enough to conduct research without making critical mistakes.

Why can't an independent researcher just go over to the lab of the original authors with a magnet and some equipment, to verify the measurements on their sample? Why are we forced to squint at blurry Bilibili videos?

They could…but they’d still have to verify the entire process was independently reproducible anyway.

"There exists one sample of a material that is a room temperature superconductor" would be a statement worthverifying, regardless of any details about how the fabrication was done or even what the material is made of. The replication would be the experiments. The cageiness about showing off samples, when they already put the preprints out there, is baffling.

Sure, but that isn't the scientific process. Typically a first team publishes what they did and the result they obtained, then others will try to replicate and improve on those results.

What you describe is interesting, but more of a closed/proprietary approach. A team says they have something and invite others to take a look, and then the second team will need to make sure they aren't being bamboozled somehow. But until the second team can actually recreate the entire situation, it isn't very useful to them. They just get to be onlookers, and will remain sceptical that there is some bamboozling being done.

Nah, it's no more or less scientific than anything else. The scientific method doesn't insist that scientists fabricate their samples from scratch, any more than they need to build their own microscopes or mine their own raw materials from the earth. People who make new materials send samples to other labs to characterise all the time; when Geim and Novoselov first synthesized graphene, they were mailing packets of the stuff to practically anyone who asked.

And in this case, a room temperature superconductor would be so striking that sending one small sample off to another lab, or even inviting someone in to check (which can be done extremely quickly) would quickly resolve a lot of issues.

Well, if the managed to replicate LK99 independently, then this won't be necessary.

Why should they? If they can reproduce LK-99, this is no longer necessary. If the case was that no-one could replicate it, but the original lab still insists, then such an investigation might make sense, either to verify them, or to find further information.

Replicating an experiment is not always easy, because it can always be that the original publisher did not provide all information. That could be on purpose, or just by accident, because there is e.g. something they don't know. Like in one case where a lab had some interesting results, and in the end it turned out that one of the ingredients were of insufficient purity.

Well, what if they've painted up some other room temperature superconductor to look like LK-99? Recreating it from scratch avoids that.

some other room temperature superconductor

A what, now? I hope you're being sarcastic.

You know, just an off the shelf room temperature superconductor that they've claimed to synthesize themselves

It's available from the physics store, right next to point masses and frictionless pulleys.

I think part of the issue is actually reproducing the synthesis. Yes, maybe eventually they will share their sample.

This is quite a counterclaim over that group who published that they could not replicate the effect. Lets see what happens next.

Not really. Even the original authors only claim a 1 in 10 success rate, so failures to replicate aren't that surprising.

Still don't know what a LK-99 is.

It's an alleged superconducting material that will work at room temperature.

Room temperature and pressure. The two are intrinsically linked.

That really depends. Offices are usually low temperature and very high pressure environments.

Ah, that one.

Ask anyone in the UK what a 99 Flake is

I want to believe. So far there's evidence that some flakes have diamagnetic properties but I don't know how long it'll take them to actually run current through it and confirm if it's a superconductor or not.

Holy shit

It's too good to be true.

Cheap, clean, common doesn't happen. The odds that they were able to manipulate a second lab to falsify data are a million to one over this being a thing. If I'm wrong I'll Venmo you twenty bucks, if money is still a thing within weeks of this actually being a thing.

What's the point in manipulating another lab with money? When confirmations or otherwise will start popping up from other labs around the world in probably days(?)

There's no such thing as bad publicity, name recognition will get a scientist pretty far.

They have seven days until doubts can truly start cropping up, then another few weeks until all but the people who really want to believe are buying in.

Can someone explain in lay terms why this is relevant? I read somewhere that it was considered as important as the invention of the transistor but didn't catch why.

Superconductors in general have no electrical resistance. That's basically electricity's friction.

Superconducting materials make the strongest electromagnets, they have big applications in quantum stuff (which I don't properly understand to try explaining), and they're used in something called a Tokamak, a specific kind of fusion reactor. They're useful in anything where electrical resistance is bad in general. When electricity is resisted, we lose some and get heat, so a superconducting wire would lose none and never heat up as a result of resistance.

Superconductors traditionally have to be super freaking cold. A lot of these applications can only be done with liquid nitrogen or even colder things, keeping them superconducting. You can do some things with pressure to help out with that, but the point is it's not easy to keep a material superconducting. This effort translates to costs, often prohibitive ones, as you need to actively keep these materials from collecting any heat.

If this research pans out, though, this kind of superconductor will just work at standard temperature and pressure. These could go into standard circuits, they can sit around without bleeding money on upkeep, they're very cool.

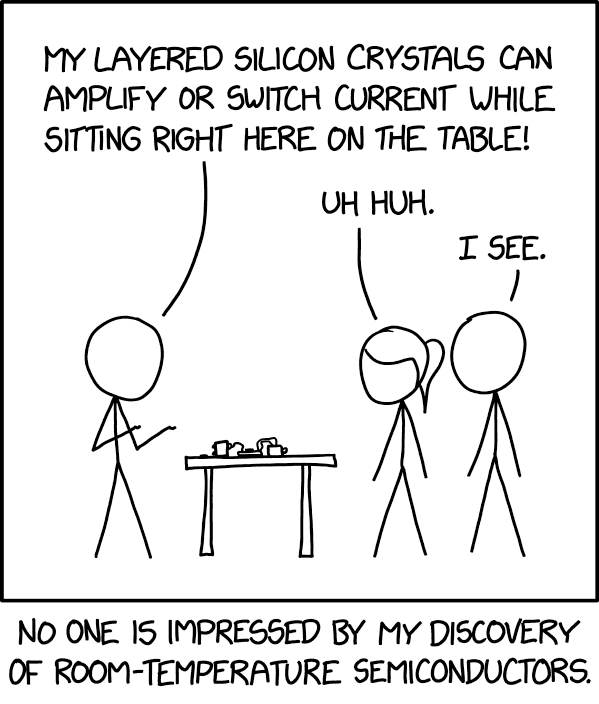

People are comparing them to transistors in part because before transistors we had vacuum tubes. Vacuum tubes do the same thing as a transistor, but they're effectively a lightbulb. They burn out, they produce heat, and they didn't miniaturize. Transistors were magic at the time because we could do so much more with them than vacuum tubes, and for superconducting metals, this is the same.

Thanks for the explanation. So, this means we are another step closer to quantum computers for example?

I'm trying to grasp on this concept and how we could see this in our daily lives. Better batteries? I thought about that because they get hot when charging but not sure if it's because of the resistance. Going into standard circuits means we'll have better SoCs? better integrated circuits? Faster computers or phones?

Im trying to think about a daily life application but maybe it won't have a direct impact on that area, maybe it's more about facilitating research that will eventually turn into daily life stuff?

Better batteries, yeah. That's down the line. We will also generate heat during the actual use of any devices. But, less.

It also could become the most efficient commercial batteries, but I expect the cost will be prohibitive. Sending electricity always has a loss, but it doesn't through a superconductor, so these will have a lot of uses at power generation sites, both reducing heat and losslessly storing it (until it enters the traditional grid).

It won't directly transfer to faster tech or anything like that, but it helping quantum computing could do so indirectly.

Definitely it's more of a facilitating research kinda thing. You can't play with superconductors in a lab in a cost efficient way, but this could let you.

Also maglevs and MRI's directly use superconductors currently, so that's a direct use, lower cost MRI's and incredibly fast trains.

Heat is a huge barrier to increasing clock speeds, so a room temperature and pressure superconductor would actually fairly directly translate to major performance gains in computing.

While true, that'd only be for a superconducting CPU. I doubt this material can both superconduct and act as a transistor, and even if it can, I highly doubt you could pack in anywhere near the amount we have in standard CPUs. So while we might replace a standard power supply with a superconducting one, and reduce heat that way, I don't see any direct computing boosts from this. We could superconduct everything around a CPU, have superconducting wires, but the heat from a CPU is generated in the silicon.

It'll be pretty nice to have 100% efficient PSUs, though. Definitely some gains there, just not the same revolutionary ones seen elsewhere.

Got it. So it'll eventually lead to develop or improve daily stuff. I hope this material becomes a reality.

A conductor with no resistance is a big deal for many electrical applications. Electrical resistance is often a big part of design. Removing that aspect changes things significantly. Electrical power losses and the size of conductors can be greatly reduced.

I've read lots of unsubstantiated claims about superconductors. A solution has to be producible in quantity at a reasonable cost. Otherwise it's not going to be a breakthrough. I mean we currently have expensive and bulky superconductor solutions, but they're limited to applications where it's reasonable such as MRI machines and particle accelerators.

An inexpensive room temperature superconductor would make the most difference in tech sectors such as power transmission, electromechanical, and power electronics. These are areas where power loss due to circuit resistance is a big part of design. The impact would be minimal for computing and logic. There may be areas where power loss can be reduced, but logic relies on semi-conductors which must have resistance to function, it's in the name. The term "semi" implies resistance.

I think it'll be first used in energy transmission.

If it's actually a thing.

One thing that you'll definitely observe in daily life is the development of fusion reactors. They're significantly safer than regular nuclear reactors (which run on fission), and also a lot cheaper (theoretically). The current downside to fusion reactors is that up until this point, it usually takes up more energy to run it than the energy that gets produced. So in other words, it doesn't actually generate enough energy to make it worth building. Most of the energy spent is trying to keep the magnets in the reactor cold enough to function. Since room temperature superconductors should function at room temperature, there will be no need to keep them cold, so a lot of the energy spent keeping the magnets cold will become unnecessary. This will significantly improve the development of fusion reactors, to the point where it is possible that we may even see fusion reactors on our energy grid in our lifetimes. Basically, if this claim is true, you can expect that energy costs will become virtually negligible and the world will almost completely run on renewable energy

Well I really hope this is real then and more importantly it translates to cheap, clean energy

Would the original team want to patent this finding (slowing the process down somewhat)?

If a room temperature superconductor can be successfully made, it would likely make them millionaires in a very short amount of time.

Would the original team want to patent this finding...

Patents were already filed in Korea and internationally.

Let him cook

ELI5 for those of us without quantum physics degrees?

Fireship's video explains it quick and easy

Two Bit explains it in more detail

Tldr: this would let us easily conduct electricity with near-zero resistance and would be the biggest scientific discovery of our lifetime if true, which it seems like it might actually be. We need more people to successfuly replicate it though, like the Huazhong team say they did.

Here is an alternative Piped link(s): https://piped.video/BPadRwJbylY

https://piped.video/PLr95AFBRXI

Piped is a privacy-respecting open-source alternative frontend to YouTube.

I'm open-source, check me out at GitHub.

That's awesome, and amazing if it can be replicated! Thanks for the summary - that was perfect!