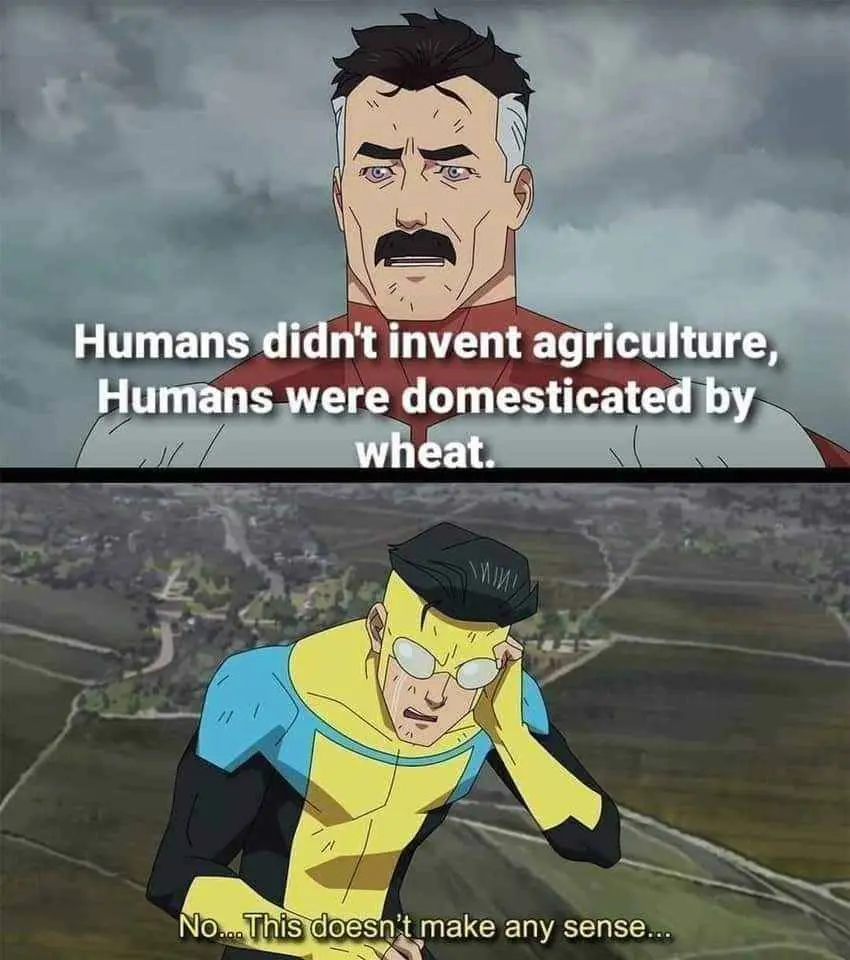

I mean, the Roman Empire was an olive tree superorganism. Prove me wrong.

Science Memes

Welcome to c/science_memes @ Mander.xyz!

A place for majestic STEMLORD peacocking, as well as memes about the realities of working in a lab.

Rules

- Don't throw mud. Behave like an intellectual and remember the human.

- Keep it rooted (on topic).

- No spam.

- Infographics welcome, get schooled.

This is a science community. We use the Dawkins definition of meme.

Research Committee

Other Mander Communities

Science and Research

Biology and Life Sciences

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- !reptiles and [email protected]

Physical Sciences

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

Humanities and Social Sciences

Practical and Applied Sciences

- !exercise-and [email protected]

- [email protected]

- !self [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

Memes

Miscellaneous

There’s a Pax Romana/olive branch joke in there somewhere

"We're taking your country over. You should produce olives. If not, then grapes. Or like, wheat, I guess. But definitely olives." - Pax Romana

Makes total sense: who's working for whom? Is wheat making an effort to till the soil and find fertiliser to help us grow, or is it the other way round?

And here we have a typical specimen exhibiting capitalist realism: Observe how the subject is analysing everything they come across on a "who works for who" basis, projecting human modes of production onto the universe. Applying it, even in vain, this reductive universality ensures that they will never think beyond it and, not thinking beyond it, not question either working for a capitalist or being a capitalist who is worked for, thereby in either case working for capitalism, a form of human cooperation in which happiness, well-being, yes even human connection (that necessitating eye-level communication) is traded for hastened advancement of the economy to achieve post-scarcity.

9 points out of 10, very good. Except that capitalism doesn't want to ever achieve post-scarcity. They're a dog chasing a car, without scarcity and demand their profit streams dry up.

Hence why post-scarcity is the natural death point of capitalism.

Your question is essentially the same as Freudians arguing among themselves about the existence of a death drive: How could it possibly benefit the individual? If it can't in some way benefit the individual, how can it be a drive? How does it mesh with the pleasure principle? The answer is simple: It doesn't benefit the individual. In certain circumstances it benefits the genome, that's why us seed-pods can, in certain circumstances, enter states in which it is pleasurable.

And all-encompassing and all-powerful, indeed, religious, as capitalism may seem right now it, too, is a seed pod. It does not have to will its abolishment to bring about the material conditions abolishing it.

Of course there's also nothing speaking against it not making things unduly nasty for us. But that's mere politics, not fate.

This is like the question I've always asked about getting sick.

Do you produce extra mucous because your body is trying to get rid of what's making you sick or does the illness make you produce more mucous in order to spread more easily?

I suspect the serious answer is that we produce mucus and sneezing as a natural response to microbes, and that's the environment within which microbes have evolved to take advantage of the mucus and sneezing

Evolution is a loop of random mutations that get reproduced if they randomly happen to give the organism better odds at reproduction.

Some germ gets a little better at spreading via mucous, so it gets to reproduce more because humans make mucous when they get sick

While I wouldn't say that's right, I also wouldn't come right out and call it wrong either. This very much engages with the "Selfish Gene", an heuristic model of thinking about evolution from the perspective of the gene itself instead of populations.

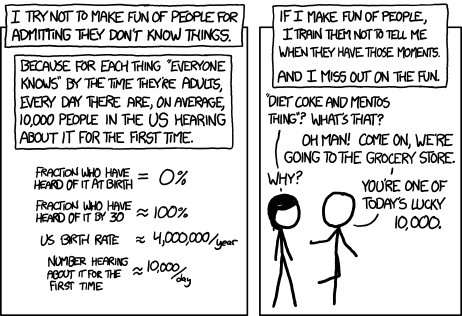

As an added amusement, the book "The Selfish Gene" came out in 1976, and is the source of the word "meme," used somewhat differently than it is now, naturally.

Just like cats right?

Just like cats.

Wouldn't the cats have also been demesticated by the wheat? Since the wheat domesticated humans, stored the wheat berries in silos which attracted mice and is the whole reason cats were like... "I live here now."

Omni-Man's red eyes make him look blazed, which fits what he's saying pretty well. "Dad, what the hell are you talking about?"

- Beer

Deleted

I so want to befriend my local crows, been meaning to buy some seeds for bribing them

We have been played for absolute fools

Well, who's living in the house? Certainly not the wheat.

You, a farmer, living in a thatched roof mud hut just alongside the field and spending 90% of your day - sun up to sun down - digging irrigation ditches, spreading fertilizer, and hauling around buckets of seed.

Me, a wheat grass, cozily settled into freshly irrigated mud, reaching towards the sun with my long fronds, spreading my seed between all my neighbors, and never having to worry about competitors because this dipshit ape-thing weeds the area for me every day in hopes of one day gargling my fermented plant-jizz until he blacks out.

Isn't this Michael Pollan's theory?

That plants make themselves Delicious/useful/whatever so we'll use them more?

Realistically the wheat lucked out that we thought it was delicious. I like the theory that it started as a three way symbiotic relationship between wheat humans and yeast, with accidental beer being the reason we started planting the stuff to begin with.

Yup! The Botany of Desire. Good read.

Focuses on how apples, potatoes, tulips, and cannabis have all been vastly successful at being spread by humans because we find them useful.

It really is a symbiotic relationship we've developed with the things we've domesticated (or that domesticated us)

Especially animals reserved for working instead of eating, because in those situations oftentimes the food being made with the work is shared between the symbiotes.

I would say it's symbiotic to the continued survival and propegation of their genes, but not to their well-being as individuals.

Yeah, influence is rarely a one way street and things like agriculture or animal husbandry have definitely changed us as well

How to tell someone is reading Sapiens.

Still, insane that "science/technology improvements" did not improve happienes at all. Just shifted the standards.

Haha. I'm reading Sapiens right now, too

I've never actually read any Harari books for some reason. Is his stuff generally "reliable"?

r/askhistorians on reddit always rails about it being, paraphrasing: too cut and dry for such complicated topics. I've the first half of the first one, and I don't disagree, but I'm not a historian. Reductionism is definitely in play, and there's certainly a narrative bias in there for entertainment.

It seems about as reliable as Isaac Asimov's essays (as published in The Road to Infinity, or similar).

Thanks. So, interesting and generally reliable, but claims should be treated with caution?

Yep.

When a historian complains that something is reductionist, I usually ask them "what is the temperature of the air in the room right now." I don't mind reductionism, particularly when ingesting materials from outside my field of expertise -- because I don't have time to become an expert in every field :)

I usually ask them “what is the temperature of the air in the room right now.”

What mean? I can't brain good today

Okay, so, temperature is a statistical measure of the kinetic energy of the atoms in a material. It's useful, so we use it. But, I'll try to handwave a lecture from Thermodynamics 300 -- the actual lecture requires quantum mechanics, partial differential equations, and a dude named Maxwell.

So imagine you put at molecule of an inert gas (helium or similar) into a perfectly insulated box, and that box (aside from the single molecule of helium) is a perfect vacuum. Now, what temperature is that molecule of helium? The question is somewhat meaningless. What we can do instead is ask, what is its position, and its velocity/momentum. For an object as large as helium, you don't really have to deal with the uncertainty principle, and can largely just treat it as a billiard ball bouncing around in there, boing boing boing.

But if you add a second helium, now you have interactions. They can both have a position and momentum, but occasionally they will bump into each other, and depending on the angles and velocity and such, they can transfer momentum into one another. Still a billiard ball scenario, and relatively easy to visualize.

As you start adding more balls though, tracking the position and momentum of each one starts to become crazy. You stop being concerned about the positions of the billiard balls, but start doing statistics -- you sample a few of them, and get some new estimates: average distance between balls at any given time, average momentum of the balls at any given time. What we're doing is moving from treating the atoms as discrete elements into treating it as a gas. For helium, it's actually quite reasonable to work the math out from first principles because it behaves so ideally. But you end up deriving a quantity known as "pressure" -- which reflects the average distance between the balls, and "temperature" which is effectively the average momentum of the balls.

But here's the thing -- just because we have an average, doesn't mean it's evenly distributed. In a real gas, there are big and small molecules all jostling about, and some are moving faster and some are moving slower. But statistically, we can treat it as a nearly uniform material because there are a lot of them.

We've reduced an incredibly complex thing to a single number or two.

Tangent: we lose some of our atmosphere to space every year, and this process is partially why. Some of molecules jostling about at the top of the atmosphere where the distance between them is quite large can sometimes bounce into one another in accidentally perfect ways such that single atoms or molecules can get to great velocities. If these exceed escape velocity, they will never return to earth. But it's more likely that these collisions eject smaller molecules, like hydrogen and helium, than larger molecules, like oxygen or nitrogen. So we lose the light stuff preferentially. Imagine the box with billiard balls bounding around it it, but some ping pong balls are there too and they can get launched! See Jeans Escape for more details if you want a rabbit hole.