this post was submitted on 24 Jul 2023

603 points (97.6% liked)

196

17265 readers

1948 users here now

Be sure to follow the rule before you head out.

Rule: You must post before you leave.

Other rules

Behavior rules:

- No bigotry (transphobia, racism, etc…)

- No genocide denial

- No support for authoritarian behaviour (incl. Tankies)

- No namecalling

- Accounts from lemmygrad.ml, threads.net, or hexbear.net are held to higher standards

- Other things seen as cleary bad

Posting rules:

- No AI generated content (DALL-E etc…)

- No advertisements

- No gore / violence

- Mutual aid posts require verification from the mods first

NSFW: NSFW content is permitted but it must be tagged and have content warnings. Anything that doesn't adhere to this will be removed. Content warnings should be added like: [penis], [explicit description of sex]. Non-sexualized breasts of any gender are not considered inappropriate and therefore do not need to be blurred/tagged.

If you have any questions, feel free to contact us on our matrix channel or email.

Other 196's:

founded 2 years ago

MODERATORS

you are viewing a single comment's thread

view the rest of the comments

view the rest of the comments

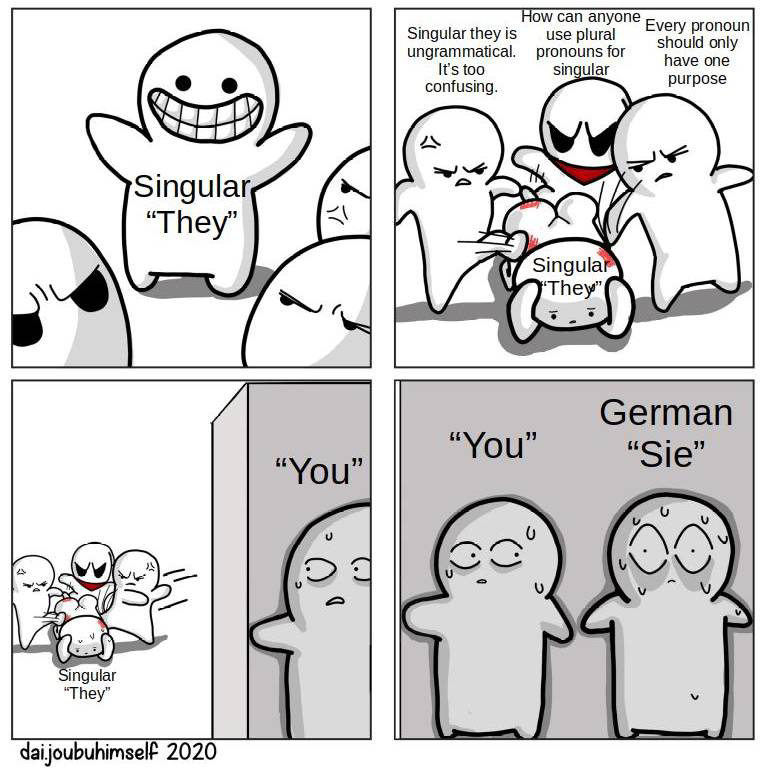

Lots of people talk past each other on this. Singular they to refer to a known single person is an invention of the last few years and is the thing that a lot of people are up in arms about. It gets confused with the centuries-old usage of using it to refer to an unknown or undetermined person. Your first example is in line with the latter, and your second example is the new usage. TBH I'd be confused by your second example. Is Frank part of some larger group that doesn't know what they're talking about? Or is it only Frank that doesn't know what he's talking about?

No, it's been used for at least 400 years.

It's actually even older than that though. It's over 600 years.

https://nyulocal.com/shakespeare-used-the-singular-they-and-so-should-you-6452240ca9e0

Your confusion here is exactly what I'm trying to clear up. We know the gender of the person in the Shakespeare quote you linked to ("man"), but nothing else. It's a placeholder term that doesn't refer to a specific, known individual. Shakespeare never said anything like "Here's Frank, they're a cool guy", that would be considered ungrammatical until a few years ago.

Just here to support: English is a constantly evolving language. By way of example, historically, the word jealous has been that you're afraid of someone taking something from you, like a relationship, it's something you have, that you may lose due to someone's influence. The term for wanting what someone else has, is envy. If someone has something you want, you are envious of them. But if you go find the definition for jealousy, it now includes that you want something someone else has, because people have conflated the word jealous with the definition of envy. What happened is that the definition of jealous changed. IMO, I'm not a fan of that one specifically, since we already have a word for envy, but it speaks to my point.

The language adapts to the common usage. Historically, they/them has been used as indirect singular/plural. The change that's happening now, is that they/them is being used as direct and indirect singular/plural. In the past, the only direct singular for an individual has been he/she/you. There was no direct singular ungendered term, besides "you", which is only applicable when the subject is the listener. Adding they/them to that is logical, the only alternative I see is to use a brand new word, one likely adapted from another language that already carries that singular and direct meaning. Authoring a new word for something like this isn't new to English either, since many English words have roots in other languages, which is why grammar rules seem to have (and often do have) more exceptions than anything (like i before e, except after c, or congugating a word with "er" or something similar).

I'm personally a fan of adapting they/them to be direct singular, on top of it's current use. While it's uncomfortable for some to use they/them in this manner, myself included, is rather make myself uncomfortable by using that, then make non-binary persons uncomfortable by using pronouns that make them uncomfortable. Besides, the definition of they/them is so close already, that this is a minor adjustment at most. It's barely an inconvenience.

Sure, that's a great discussion to have, and I'm glad you spelled it out well. I just dislike people trying to claim that using "they" to refer to a specific, known individual is "nothing new because Shakespeare did it". He didn't, and it muddies the waters of the conversation to spread falsehoods like that.

I get that. Irrespective of if Shakespeare used they/them in this way or not; I would challenge anyone to even have a conversation about someone, or tell a story and not use they/them to describe a singular individual. Fact is, it's so common in speech, that people breeze past it without thinking about it, because it's natural to use they/them as the indirect singular. Everyone has used they/them this way, and continue to use those words this way, without even realizing they're doing it.... like I just did.

The discussion of when/where/who started it, isn't really material to the point that almost everyone uses it in this manner right now, even if they're not introspective or analytical enough to realize they're doing it.... so I would argue that it's not relevant to focus on the who/what/where/when/why of the use of the words in this context, but rather focus on what's happening now.

Leave the discussions of who/what/where/when/why/how to the historians and the linguists. I agree that such discussions just muddy the waters of the reality of what the common usage of the words are, and therefore it should be set aside and left alone; at least by anyone who doesn't hold a PhD in English literary studies or something...

It's not a thing of the last few years I've been using it for at least a decade.

A few years is a loose term, but it was certainly not in use by Shakespeare, unlike what people try to claim.

To be clear, this example, where the singular they is used for a person of any gender, is confusing to you.

Based on the above questions, the confusion is about attempting to identify if the singular they or plural they is being used.

But these variants with a person with an ungendered name or description are fine. Example with ungendered name:

Bob - “Hey Jo, Kelly thinks we should tweak widget X.”

Me - “Yeah well, they don’t know what the fuck they’re talking about.”

Example with ungendered description:

Bob - “Hey Jo, the engineer thinks we should tweak widget X.”

Me - “Yeah well, they don’t know what the fuck they’re talking about.”

If that is true, that the second and third examples are not confusing, then determining whether the singular they or the plural they is being used is not the source of the confusion. As in all three examples, we have a person who was previously referenced excluding the possibility of the plural they. In the first example Frank, in the second Kelly, and the third the engineer. All that has changed in the first example is that the singular they has no restrictions based on name or description. If that grammatical distinction is the source of the confusion, so be it, but let's be clear on what the confusion is.

Source I used to unpick this, specifically the first table in section 3: https://www.glossa-journal.org/article/id/5288/

Your Kelly example is similarly confusing. The "engineer" example is also confusing, but because English already conflates those two meanings, I at least know that I'm parsing a confusable sentence and can pick up on context clues.

If I were writing that, I'd say "Yeah well, that engineer don’t know what the fuck they’re talking about." The "they're" is then not confusing at all.

In this example, the engineer is the antecedent, the thing that is being referred to previously by the pronoun they. The only difference between the above example and this example

is that the antecedent is in a previous sentence said by a different person. This is a common use case for pronouns in general during a conversation and also a common use case for the singular they. My point is this is not confusion related to the most recent change to the singular they, that restrictions to name and description have been lifted. That's fine, but I think a lot of what people are saying about Shakespeare is relevant to this particular form of confusion, singular they vs plural they, because we have been using the singular they for quite some time.

The root of the problem is that it's an indirect reference to an individual. They/them is commonly (until very recently) referring to a party (singular or plural) that isn't present. When you use it as a direct reference to someone who is present, most people feel like it's incorrect because of the common usage of the term being indirect.

When speaking to someone about Joe: "Joe doesn't know what they're talking about" While directly: "Joe, you don't know what you're talking about"

Both are correct, and possibly the most correct forms of the statements. Substitute Joe for whatever name and it still works. Meanwhile, it's uncommon, in Joe's presence, when not taking to Joe, to refer to (assuming Joe is using gendered pronouns) him as a he/him. "Joe doesn't know what he's talking about"

Both cases are singular, but the difference of Joe being there changes "they" to "he", and not taking directly to Joe changes "you" to "he".

The problem isn't plural vs singular, the problem is direct vs indirect reference.

To the best of my knowledge, using pronouns like he, she, they for a person who is present in the room during the conversation is not part of the most recent change to the singular they. That would be confusing, but I am not aware that that is happening. He, she, and they are still only for indirect references to a person as far as I know.

I don't think you're wrong here; it's just uncommon to refer to someone as they/them even indirectly while they are present and engaged in the conversation that's happening, but may not be the directed recipient of the statement. In almost all cases, at least until recently, the pronouns he/she or him/her would be used instead; therefore it's sort of awkward to use it as a direct pronoun in that context; but using they/them as a direct singular is not new in any capacity and I believe you're correct on that. It's just uncommon, and IMO, would generally come across as mildly dismissive or insulting toward the individual in question.

I believe the (former) dismissive/insulting nature of the context of referring to someone as they/them directly is the root of the discomfort most people (especially cis-normative persons) have around using the term for direct reference of a singular individual. Their brain is uncomfortable at the fact that they're using (mildly) offensive language towards someone who they likely mean no offense to, meanwhile to use he/him or she/her instead is likely going to be far more offensive to someone who is non-binary, so the discomfort only lies within the speaker and their expectation of how what they are saying will be understood.