science

14984 readers

665 users here now

A community to post scientific articles, news, and civil discussion.

rule #1: be kind

<--- rules currently under construction, see current pinned post.

2024-11-11

founded 2 years ago

MODERATORS

76

77

287

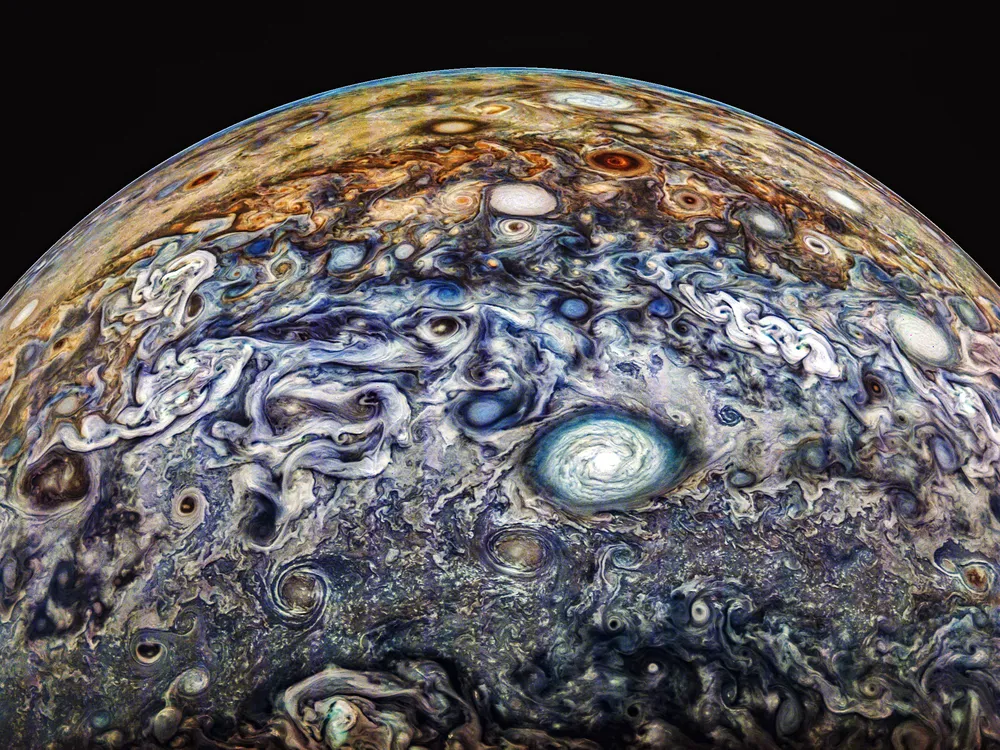

Check Out the Stunning New Images of Jupiter From NASA's Juno Spacecraft

(www.smithsonianmag.com)

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

158

In a First, Scientists Found Structural, Brain-Wide Changes During Menstruation

(www.sciencealert.com)

90

91

92

57

Paid to Peer-Review: Physicians Reviewing Top Medical Journals Receive Billions from Pharmaceuticals

(reformpharmanow.substack.com)

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100