this post was submitted on 19 Feb 2024

529 points (97.3% liked)

Greentext

4881 readers

830 users here now

This is a place to share greentexts and witness the confounding life of Anon. If you're new to the Greentext community, think of it as a sort of zoo with Anon as the main attraction.

Be warned:

- Anon is often crazy.

- Anon is often depressed.

- Anon frequently shares thoughts that are immature, offensive, or incomprehensible.

If you find yourself getting angry (or god forbid, agreeing) with something Anon has said, you might be doing it wrong.

founded 1 year ago

MODERATORS

you are viewing a single comment's thread

view the rest of the comments

view the rest of the comments

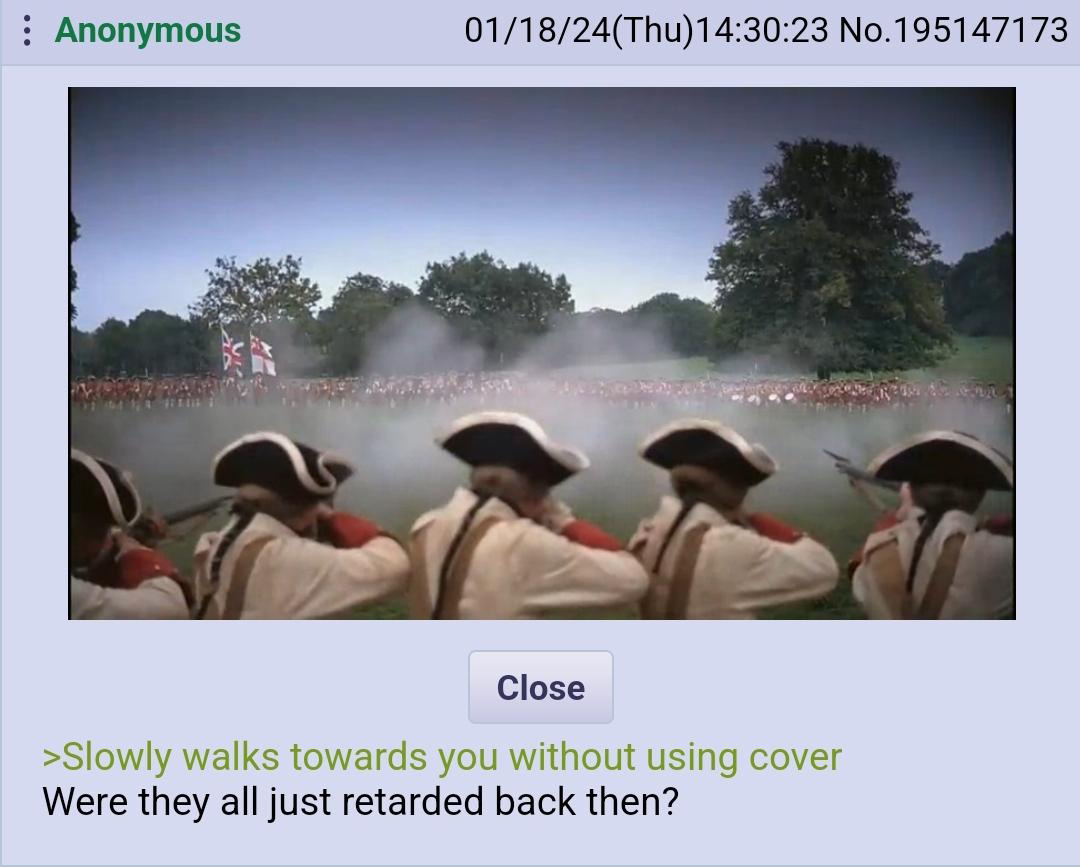

So, from what I remember from history, this was widely used by British forces right up until the invention of the machine gun by the Germans. Once you could deliver a large number of projectiles down range very quickly from a single position, this was an insanely stupid strategy. Before that, most rifles were very slow to load and fire, and had the accuracy of a storm trooper.

By lining up like this you would create a dense "cloud" (if you will) of projectiles every time the commander would yell "FIRE!" Making it far more likely for something to land on an intended target (whether that was the target being aimed at or not). Additionally, it wouldn't just be one row of soldiers, more like 5+ rows of soldiers in this formation. When someone inevitably gets shot, the next soldier in line would step forward, over their dying friend to take their place. The result was a wall of firepower that worked very effectively in field combat.

More soldiers = more guns = more projectiles going down range for the enemy. If you wanted to be effective in the field, having more bodies to throw into the battle was a way to ensure success.

Once the machine gun was invented, one small troop of 3-4 soldiers could effectively counter this maneuver by simply holding down the trigger and panning across the field of battle half a dozen times. Which is when trenches and fox holes were the preferred way to ensure you didn't lose your entire military trying to fight the enemy. With the improved accuracy of weapons and the invention of automatic fire, these battle tactics only spelled failure for anyone attempting them. Suddenly having cover either in the form of a trench or sandbags or something, was the only effective way to ensure you didn't get "mowed down".

In the modern era, field combat is a complex operation of coordinating troop movements and directing them towards the enemy while maintaining cover to protect the lives of the soldiers. Somewhere between radio and high accuracy assault rifles is where modern combat exists. Keeping in communication with your team while coordinating your movements, and accurately firing at the enemy as you go is now the norm. In times between WW2 and the modern (electronic) era, you would use code names and reference places with specific, agreed upon alternative namings for locations. Once cryptography became efficient enough to be portable, encryption has become favorable to increase the security of communications and clarify names and locations by using more plain language while protecting that information from eavesdropping. Before encryption and digital transmissions, everything was either AM or FM voice (not dissimilar to AM/FM radio), and could be intercepted or listened to by any person, friend or foe, with the equipment to do so; the only option was to use namings that would obfuscate the intention, locations, attacker, and size of force from anyone who may be listening in.

The cypher/cryptography of the age was fascinating, and "both sides" employed code breakers to try to understand the messages being sent. It's very fascinating. As an amateur radio operator, I get what they were doing, and it employed some very clever tactics, which had varying degrees of success. Now it's just a matter of using a digital encryption cypher to encode any communications (not dissimilar to what is used for secured websites) which is nearly impossible to break without significant time and effort, and usually by the time the cypher is broken the operation is complete and the codes have been changed. Being an IT person by day, and knowing how those cyphers are generated and used, it would be nearly impossible to "crack" in a reasonable time frame, even with even powerful supercomputer hardware. The modern digital and military communications systems are only really countered by employing jamming technology to scramble legitimate signals with noise. The only counter to such jamming is moving to a channel which is not jammed, which may be impossible with limitations to the equipment that is employed in field operations (they generally have a fairly small operational frequency band, which they cannot exceed), however, with software defined radios and multi band radio transceivers, this limitation is getting easier to overcome. However setting up multiple jammers to cover the useful radio bands for long distance communications, is becoming easier at the same time (generally bands below 500Mhz or so). The arms race to find ways to overcome these problems is far from done though.

But now I'm way off topic.

Well written and all.

However I'd like to point out that even modern warfare, despite how much it's changed (take for instance rather basic troops having access to small drones to drop grenades with into foxholes and trenches), kinda the basics remain: you have men advance to a position by any means necessary.

Since, idk, thousands of years ago when first actually organised militaries appeared, the basics — or "the game", if you will — has been very much the same, but the technology changes "the meta."

When I was sitting lessons in the army in 2009, most of us were wondering why we needed to drill such basic strategies and tactics, and why would they ever matter, because the enemy has thousands of nukes. The lieutenant explained rather well how despite modern weaponry and technology, a lot of the basics of war are still very much the majority of it.

Like for example the Gatling gun made this strategy quite bad, but the Gatling gun wasn't instantly everywhere. It's not like with videogames where the whole game is patched and everyone has to use the new meta because everyone has the same rules. Unlike in real life, where the "meta" changes slowly and not everywhere all at once.

And where one reliable thing is that in war things like new tech can't always be relied upon.

Wars are just so futile nowadays. I get that global cooperation was a practical impossibility even just 50 years ago, but nowadays it really isn't. Case in point, I have no idea which country's army you the reader thought of when I said "army." With probability, American, but I actually talked about the Finnish one.

I've also veered quite far from the original point. Here, have some Doctor Who as compensation:

The Doctor: Because it's not a game, Kate. This is a scale model of war. Every war ever fought right there in front of you. Because it's always the same. When you fire that first shot, no matter how right you feel, you have no idea who's going to die. You don't know who's children are going to scream and burn. How many hearts will be broken! How many lives shattered! How much blood will spill until everybody does what they're always going to have to do from the very beginning -- sit down and talk! Listen to me, listen. I just -- I just want you to think. Do you know what thinking is? It's just a fancy word for changing your mind.

Case in point, the Germans had an automatic "rifle" if you still (machine/Gatling gun), before the allies in WW2. Guns of the era were far more accurate than the muskets used during older conflicts like the American civil war, but were far from automatic; to my best understanding of it, most were barely semi-automatic and had very limited magazine capacity, often only a handful of round at most. This was a massive step up from the single shot muskets used in previous battles but would not stand up to modern versions of the same which are often more accurate, can fire at much faster rates, and can have a lot more ammunition per magazine.

Looking at schematics of current era rifles, the designs seem so primative compared to the intericacies of other common modern items, like computers and smartphones, but still, even this level of technological advancement was far out of reach of the people from that era. The technology really took off when we started using jacketed self contained rounds, which were easily changed out by mechanisms rather than having to do so by hand (such as with a revolver versus a more modern semi automatic pistol).

I understand why firearms are kept so primative compared to our current level of technology, since they are required to have a high level of reliability and resilience to interference, maintaining a fairly simple mechanism rather than a more complex electronic firing mechanic is preferable. So called "gas powered" weapons have been proven to be effective, reliable and resilient.

I know that more complex systems are used in weapons like missiles and drones to great effect, at the cost of reliability, more or less. The fact is, if you lose a drone or missile which has been launched or controlled many hundreds or thousands of miles away, you've only lost equipment. That's not ideal, but it's better than losing your personnel who represent hundreds or thousands of hours of training, and cannot be replaced on an assembly line. Simply put, human assets are a limited resource in any conflict, so the fewer losses to manpower, the better the outcome regardless of all other factors, since a new drone or missile can be created in a week or a month (even six months or more) which is less time than it takes to make a new person, allow them to develop to the point where they can capably hold and fire a weapon, then train them.... A process that can take upwards of 20 years or more.

In previous eras of battle, there was no choice but to put lives on the line for battle. No alternatives existed, and in the cases of field battle, alternatives still don't exist for man to man combat.

I appreciate the quotes from the doctor. It's nice to see them in the wild. I personally don't believe armed conflict can accomplish anything productive, and should only be used against those who will use it against you (aka, for defense). In the current era, we have the technology to discuss and resolve conflicts without violence, whether through peace talks via telepresence, or over more common communication technology, there's few places where communication isn't possible. Every effort should be made to solve things diplomatically, and only failing that, should force ever be considered.

We're at a point in warfare where we can seriously damage the survivability of humans on Earth, and doing so through warfare seems like a foolish thing to do. Especially if the reason for such conflict is something as idiotic as land ownership or material goods. Global trade has made such things unnecessary. We should be focused on moving forward to an era of peace and cooperation, since society is no longer bound by the trappings of the old empires, where food and land scarcity was significant and having more airable land was critical to survival. We should be pooling resources to bring better living to all peoples of the world. Yet, some are still stuck in the old ways of grabbing power by any means necessary.

And I'm off topic again. Oh well, it is what it is. Maybe some day we will learn that we don't have to fight eachother for the ability to survive.

I think you're referring to the MG 42, which was feared by the allies. as it had such a massive firerate, and despite being inaccurate, was still pretty effective, and definitely demoralising. The Stuka divebomber sound we all know is there solely for the purpose of scaring people. The planes had "Jericho Trumpets" to make the terrifying sound. So the Nazis aren't unfamiliar with terror tactics. With that I'm trying to point out that while the MG 42 was effective and feared, it was pretty much effective because it was feared, not because it was somehow technology the allies didn't have.

The Allies had for instance, the Vickers K gun, capable of similar and higher rpm. The MG 42 suited the strategies of the Germans, but not so much for the Allies, so similar guns weren't really used by infantry, despite the tech being there. They had some of those on planes to protect bombers from fighters. For that, a really high rpm and some inaccuracy is great.

Well, one is electronics, and the other is firearms. You're really comparing the complexity, yes, but the guns being somewhat simple don't make them primitive. Some of them are actually pretty astonishing feats of engineering. Putting together some metal in a way that you can then blow up the metal contraption in a way that doesn't break the contraption but propels a projectile at something. And doing it so well you can use it literally thousands of times before even having to mend the contraption.

But yeah, it is inane that we still focus so much time on this completely inane business of firearms. There's really no need, if we can all be adults and just not shoot each other. I'll much rather focus on the information technology. It can be weaponised as well, if need be, but it isn't so inherent to it's nature.

Well, I mean, sometimes "gas powered weapons" do actually mean weapons propelled by pressurised gas, not explosives. Eg air-rifles. Which sound like kids weapons, but are far from it, and were actually used in war since the earliest firearms. Here's The Girardoni air rifle from 1779. A repeating air rifle with a 20 shot cartridge. It had a manually pumped reservoir that gave the gun the power to shoot 30 shots effective at a 125 yards (114m). 50 caliber balls, at about 600 fps (152 m/s) muzzle velocity. Proved too difficult to manufacture the reservoirs and required extensive training as it wasn't a common weapon. Would've had better technology, but economics and lack of training prevented it from becoming "meta".

That very much depends, tbh. Of course the troops are priceless, but... also, they aren't. Sure yeah, a person becoming a person takes a long time, but training a person to hold a gun and fire isn't too hard. During war, some equipment definitely are more expensive than some people. Which is why some people only get two weeks of basic training and the bare necessities, while others get to fly hundred million dollar planes. The training of those guys, now that's expensive, because you need the equipment to train them with. To train a frontline grunt, you just need the gun they're gonna be shooting with. And some good boots.

However, just pushing grunts out, as a strategy, isn't really a good one long term. Case in point; Russian orcs.

Which kinda brings me back to the point that the game is the same underneath, try to get boots on the ground in a place you wish to rule over or something. The tools change. When the tools are lost, tactics devolve.

“I know not with what weapons World War III will be fought, but World War IV will be fought with sticks and stones.” ― Albert Einstein

The guns were quite accurate. They had rifling etc long before the Maxim gun.

Being a top grade British rifleman required hitting a 3 foot wide target at 900 yards or something. That's pretty fucking good without glass optics.

They were slowish to fire, but they had paper cartridges that made it not too slow. Lower casualty rates probably have more to do with soldiers not being brainwashed yet, lots of people didn't actually shoot to kill. Compare the casualty rates of the colonial campaigns where soldiers didn't consider their enemy human.

I'm not a usian but I do know that in one of your various wars some dude bought heaps of pom guns but not the right bullets for them so they got some terrible reputation for being unreliable because the bullets didn't work.

The Baker's was rifled, hence the name. I mean tbh from standing/crouching with ironsights on a real day it would be impressive today to shoot someone at 370 meters with one shot using a modern gun and these things were heavy as fuck. Idk specifically how that gun performed but we have a tendency to assume past tech was much worse than it actually was.

The colonial campaigns didn't have an organized or well equipped enemy

Um people in India were well equipped and organised at least, idk about the rest. Hell the 1857 war for indepence was using the poms own training and weapons against them but long before that the various and sundry kingdoms did alright.

The British empire and their trade companies were just absurdly bloodthirsty and inhumane.

TL;DR - when your guns are really inaccurate (like, give or take a meter), putting a bunch together increases the odds you'll hit something. If you spread them out, you'll hit less stuff. Modern guns are a lot more accurate, so cover makes more sense.

Oh ! I have a history question :

Every time is watch a movie about some war in the USA, with their inefficient guns and all, there is guns, there is bayonets, there is swords but where are the arrows and bows? How come there isn't any depiction of such an efficient weapon ?

Speaking as someone who has archery experience, it's a lot more skill oriented and has a lot more variance in field combat. The shots, while they can be quite fast, are not nearly as quick as a bullet. The skill with firearms tends to be with long range shooting. At short range, you can point and shoot and generally hit something. Even at 50m, a minimal amount of training is required to get to be accurate at that range especially with newer weaponry.

This may or may not factor in, I don't know, I'm not a history buff really, I know technology more than anything.

Personally I feel like the most contributing factor is that a bow is a comaritively fragile weapon. Most firearms are metal with wood grips. The core of the weapon is metal, and comfort aspects of it are wood.

Compare that to the requirements of a bow, where every part, aside from the riser (where the grip and sights are) needs to be flexible. The limbs, which are the upper and lower arms of the bow, need to bend and flex to provide the reaction force to fire the arrow, the string needs to be very flexible, but strong enough to handle the weight of the draw. Every part moves, bends and flexes as the weapon is drawn and fired. That flexibility introduces a lot of risk in terms of damage on a highly dynamic field of battle. At one time we had no alternative, and bows when weilded by trained archers, were a formidable force compared to the alternatives, which at the time were mainly knives, swords and shields.

The likelihood of a tool like a bow becoming damaged in the field (a limb breaking, a string breaking) whether through regular use, or intentionally by the enemy, or even by negligence, in stepping or sitting on the bow, is not trivial. Factor in that when a bow is at "rest" it's still under tension, and you can be hurt by the string or limb breaking unintentionally, especially if you're in the middle of a draw, and the difference is pretty clear in terms of operator safety. With a gun, whether a musket, rifle, or something else, generally you have fairly think iron or steel containing the discharge of the weapon. While misfires are still possible and the consequences of a misfire can be much more severe, they're far less common. I've seen people shatter arrows, sending fragments of the arrow shaft into their hand and requiring significant medical treatment; on a battle field, if you get a bad arrow that splinters when you try to fire it, which wouldn't be as uncommon as you'd like, then that Archer is out of combat for weeks or months. It's far less common for a firearm to have a similar catastrophic failure. Again, not impossible, just far less likely. It's far more likely to have a firearm jam or misfire in the sense that it fails to fire, than for it to fire in such a way that the operator is injured. There's small issues with the safety of an operator when it comes to firearms, beyond the obvious of shooting yourself, such as getting bitten by the slide (common on modern pistols), or impact injuries from not bracing properly for a weapons kickback. But given the limited amount of propellant in a bullet, it's far less likely to "blow up in your face" so to speak.

Given operator safety, and the relative ease of training (at least compared to archery), and the consistency of the performance of the weapon, operator error is effectively reduced to loading and aiming the weapon. The effects of operator errors is also reduced.

Factor that in with the lethality of firearms versus archery, and the accuracy, especially at long range, where an archer would need to factor in wind and gravity, at far closer range than a rifleman would, and the advantages are now far outweighing the negatives of firearms.

The benefits of archery is generally in the ability to reuse ammunition, the relative silence of the weapon, and the light weight nature of the materials used in archery. It's a good way to hunt and fight, but when it's compared to even (relatively) primative firearms, it doesn't really have the ability to compete. Most even better than average archers don't usually loose more than an arrow a second on a good day; once jacketed rounds became common and semi automatic rifles and firearms became commonplace, even a relatively poor rifleman can release more than one shot per second. So for shooting speed, either train for thousands of hours to become an expert archer, or pick up a revolver and squeeze the trigger as quickly as you can.

Firearms are simply better, easier machines to deliver projectiles down range in almost every comparison.

Thank you for taking time to write this explanation.

The Comanche were some of history's finest horse archers and it required the invention of the repeating rifle to end their supremacy of the plains.

There could have been a much stronger Spanish influence on the plains of North America had the Comanche not been there to turn their empire back.

TIL

You'll likely see bows and arrows in just about any movie that has Native American tribes as one of the belligerents.

I learned a lot today.

the last part isn't really true, you just can't bruteforce modern encryption, I'll maybe write some more about it later, but I'm in the train and tired, so I'll justify my statement by mentioning enigma and allan turing (the movie about him is great btw)

EDIT: yes, you can bruteforce good modern encryption, you just won't live long enough to see the results. and I'm talking about equiptment from the same area, ofc you'll be able to bruteforce todays encryption in reasonable time with computers in 10 years

Yes, "The Imitation Game" Is one of my favorite movies ever, and I don't even like bio films. I highly, highly recommend watching it; Benedict is brilliant in it.

You can brute force encryption however modern encryption methods makes it so it'd take longer than the heat death of the universe. The whole reason why DES isn't used and why it's recommended to set your RSA key length to 2048 bits is because some kid with a couple of GPUs can run hashcat and brute force your key. But hey it's still a viable attack vector because companies keep won't learn.

The thing is that you actually CAN brute force modern encryption. It's just that this process will take thousands if not millions of years. The analysis of encryption safety is based on mathematical prediction on how long it will take to crack the data. But all and every encryption method can be brute forced.

Well, you can, it's just a stupendously bad idea; but it also depends on the encryption used.

To take an example from my own expertise, WEP, or "wired equivalent protection" (ironic name), was based on a temporal cipher. Which means every transmission would rotate the encryption to avoid any kind of eavesdropping. WEP specifically had a lot of flaws that were found and it's now basically useless due to the design of how it initialized the exception (also know as initialization vectors or IV's), but the idea behind doing that was sound.

Modern SSL, or more specifically TLS scription frequently uses AES keys. It's all well defined by PKI, so I'm really not going to say anything new here, but it uses a large (usually 2048-4096 bit) static, but asymmetric key pair, where one side can decrypt the information encrypted by the other key, and vice versa. In secured HTTP, this is used to generate a session key, which is usually much shorter, commonly AES-256 (256bit) which can both encrypt and decrypt the same data, aka a symmetric key. The client downloads one of the keys from the key pair from the target site, known as the "public key", which is used to encrypt the seed for the AES symmetric cipher, and send it to the site, which uses the other key, known as the "private" key, to decrypt it and start the symmetrical encryption session.

The key is thrown away after a timeout, or at the end of the season, whichever comes first. It's done this way with computers because the asymmetric keys are generally very computationally intensive, while symmetrical keys are far less computationally intensive. They're also less secure due to the relatively short length of the key.

Asymmetrical keys usually have a validity of a year, and symmetrical keys generally have a validity measured in hours (actual length may change from connection to connection).

When it comes to the radios I've worked with, AES is a valid option for encryption. And using an AES key with the radio, both sides generally get the same key (a symmetric key), so you can subscribe as many radios to the same channel as you need. Again, symmetrical keys are generally fairly short, so swapping them out regularly is required.

If a bad actor gets ahold of the AES key in use, or can otherwise guess/brute force the key, they can eavesdrop.

Bearing on mind that my understanding of this encryption is based on my experience with commercially available civilian radios. Radio units used for encrypted military or government likely has superior encryption types and methodologies compared to what I have access to, and using temporally bound ciphers would not be an impossibility. When the cipher is regularly changing automatically, in the case of a temporal cipher, breaking it becomes far more unlikely and may prove impossible with current technology since you wouldn't be able to collect enough information during a keys lifetime to reliably predict what the next cipher will be (unless that information is encrypted using the in-use cipher).

To me, it's conceivable to use a rotating cipher based on a temporally changing seed which only the radios which have been programmed with the temporal seed would be able to determine, similar to how TOTP works (the six digit codes from apps like authy or Google authenticator), which would be used to generate the next key based on the current time and the temporal seed. No over the air transmission of the ciphers would occur. You could break each key individually by brute force, but doing so would consume an insane amount of computing power and time, making such an effort extremely impractical.

I'm not fully up to date on what ciphers are in common use in commercial/military radios, since I am not a professional radio operator, nevermind one that would require such elaborate encryption.

The fact remains that while extremely impractical, to the point of being insane to try, almost all digital encryption can be brute forced. WEP was broken by a handful of fundamental issues in the original design. Modern WiFi encryption is usually vulnerable to someone basically using a table of guesses to find the passphrase (also known as a rainbow table). Even without all that, deciphering any encrypted bitstream only requires an understanding of the cipher in use, and enough time and effort to try every permutation possible of the cipher key.

Given that cipher keys are quite long, at least 256 bits, even with a very powerful computer, or cluster of powerful computers, it would still take a very long time to brute force the code. Nevertheless it is possible.

It's insane to try, but it's still possible.