this post was submitted on 13 Feb 2025

880 points (99.1% liked)

Science Memes

12345 readers

1528 users here now

Welcome to c/science_memes @ Mander.xyz!

A place for majestic STEMLORD peacocking, as well as memes about the realities of working in a lab.

Rules

- Don't throw mud. Behave like an intellectual and remember the human.

- Keep it rooted (on topic).

- No spam.

- Infographics welcome, get schooled.

This is a science community. We use the Dawkins definition of meme.

Research Committee

Other Mander Communities

Science and Research

Biology and Life Sciences

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- !reptiles and [email protected]

Physical Sciences

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

Humanities and Social Sciences

Practical and Applied Sciences

- !exercise-and [email protected]

- [email protected]

- !self [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

Memes

Miscellaneous

founded 2 years ago

MODERATORS

you are viewing a single comment's thread

view the rest of the comments

view the rest of the comments

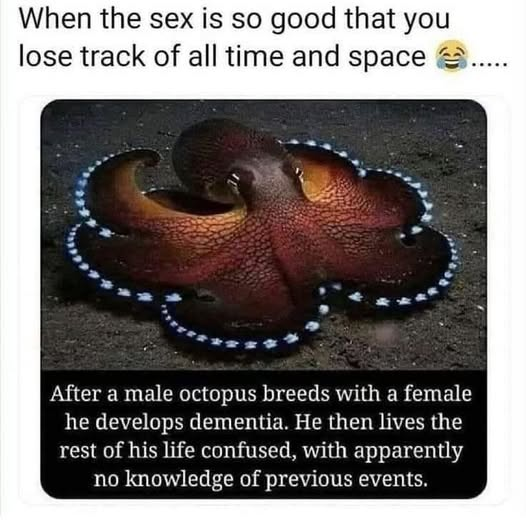

There's a specific life history strategy called semelparity, which is what you're describing (breeding once then dying). To my understanding, this is incentivized if the chances of getting a second attempt to breed are too low, and so it becomes more evolutionarily advantageous to simply go all out on the first attempt

Thanks, one solid answer! It could be that it used to be an advantage at some point and now it's just perpetuated

To be clear, it's still an advantage and for the ones that it isn't they don't die after mating. Most cephalopods are both predators and prey that life cycle results in a very high mortality rate. If you don't hunt enough, you fail and if you get eaten you fail. The deep cold water ones though, tend to have to live longer due to less prey and have fewer predators so they tend to not die after mating.

Semelparity: “Fuck it, I’m gonna nut to death”

A bit similar process in sea-dwelling salmons: migrating from salt water into fresh water (quite a big metabolic challenge in itself), traveling up rapids to suitable spawning places (often a long and arduous journey)... after they've accomplished that, their chances of returning alive are quite low. So they mostly die. But their close relatives, river-dwelling trouts spawn many times in life, because their migration isn't as costly.

I would suspect that something in how octopuses reproduce has an element of "return being costly" - it could be a metabolic return to the feeding and growing state instead of a physical return.

That makes sense, if there is an organism that is a very good predator, and the chances to breed a second time are too low, then if the organism doesn't die it will be consuming the resources of those who can breed. Natural selection must prioritize having descendents over long living, because not having descendents is extinction.