My mama always said old crater rims was like a box of chocolates. You never know what you're gonna get.

Regular readers will remember the "white rocks" that Percy was spotting in little clusters a few months ago, which Mars Guy, among others, was speculating might be quartz. The paper confirms that the first rock examined in detail in the video does contain that mineral, and is not simply another whitish mineral you might expect to find in this environment, like gypsum.

Part of the significance of this mineral being identified is the fact that it seems to comprise most of the rock being analyzed. Quartz-like material ("silica") has been discovered by Spirit, Curiosity and even Zhurong, thousands of km away from Jezero Crater, and Percy itself has already identified some in Sample 24, which we grabbed down in Neretva Vallis. Finding this much silicon dioxide, in multiple forms, in a rock that appears silica-dominated, however, is something new. That's water activity on another level - this is basically very refined silica that nature has cooked up. As the paper mentions, it would be very, very sweet to find an exposure of the source bedrock for these loose pebbles and cobbles, because that stuff we could drill for return to Earth.

Shortest answer: quartz has to be separated from other rocks/minerals. Water action is one of the easiest ways to manage that. In addition, opal/chalcedony is actually quartz with water directly attached on a molecular level, so that's a direct discovery.

Medium answer: Igneous ("volcanic") rock already contains the silicon and oxygen that quartz is made of, but they're usually bonded with other elements, not just each other. In other words, they don't exist as "free quartz" - meaning independent grains that are made of pure SiO2. As @athairmor alluded to, free quartz can form directly from magma when it solidifies and forms igneous rock. However, that is what you would expect from particular kinds of volcanic rock, which are absent or rare on Mars (e.g. granite). The igneous rock around Jezero Crater is not the type to contain "free quartz". If the regional geology hasn't served up any free quartz grains directly, you can still separate out the silicon and oxygen by breaking down the larger, more complicated minerals they're attached to, but that would take a significant amount of chemical breakdown - i.e. significant amounts of water. This process is quite common on Earth, of course, where it yields up "white sand" on beaches - which is simply rounded grains of quartz.

Longest reply: I should probably just read the EPSL paper, and I'd be happy to summarize it here if people are interested.

So that means all four sampling attempts made here on Witch Hazel Hill have been difficult in some way. Two of the attempts were outright failures, the last successful one only filled half the tube, and this latest one, #27, "overflowing" to the point of rendering the seal difficult.

I count four "difficult" sampling operations from the entire mission prior to reaching the Hill (Sample 1 an outright failure, Sample 15 difficult to seal as Mars Guy refers to in the video, and two outright failures on the delta fan around sol 810-813), maybe five if you count that problem with the pebbles getting stuck in the bit carousel after successfully snagging Sample 6.

It may have taken 37 sols, but they finally did seal Sample 15, so I'm not overly worried about this problem with Sample 27. What I find striking about all of this is the intersection of the geology with the engineering. The problem we encountered with the very first sample (the stuff simply crumbling and escaping the tube before we could seal it) was a warning shot to the rover operations team, but a fascinating sign to the geologists: this stuff has seen some serious alteration since it was originally laid down! And that weak, friable Sample 1 material saw much less transformation by water, mineralogically speaking, than Sample 27...

We knew that we were going to find igneous ("volcanic") geology combined with sedimentary geology (old river mud and sandstone) on this mission, but the intersection of the two giving us these kinds of problems is going to become part of the legend of Mars exploration. It may not be as controversial or unexpected as the Disappearing Methane Hunt or the Viking-era "biosignature" tease, but this sampling difficulty shows us just how tricky Mars is going to be.

Given this Mars Guy episode and the unusual interest that the science team is showing in the tailings (drill debris) for this latest core sample, I've created a quick-and-dirty guide to the tailings produced at the various secured-sample sites to date.

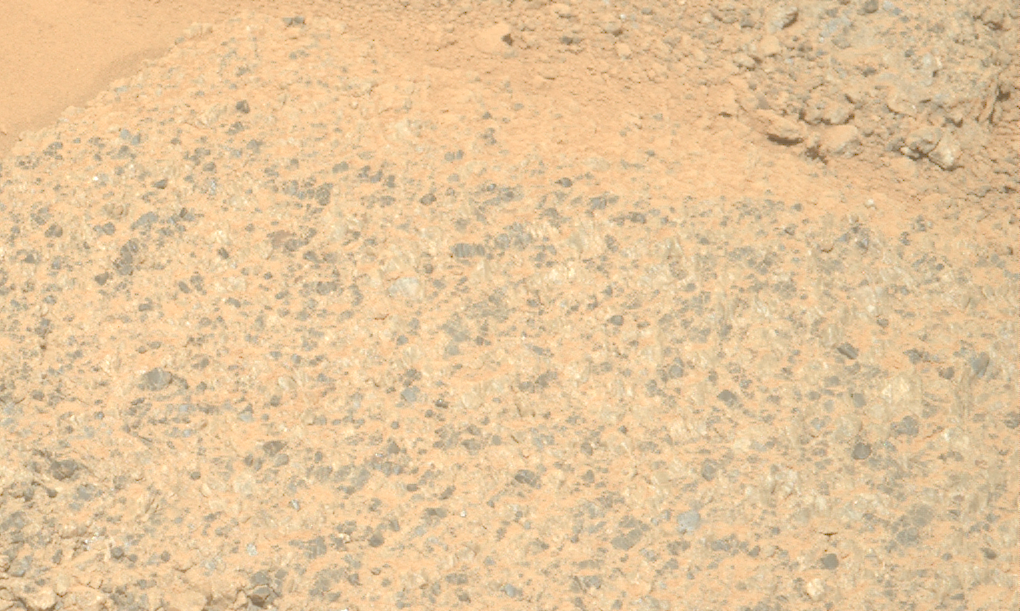

I don't have too much to add in terms of analysis here at the moment, but I will say that the tailings from the crater rim (#26 and #27) are notably brighter than almost every other tailings pile taken earlier (down in the crater). Tailings from the same environment (e.g. the crater floor, the top of the delta) tend to look similar, despite their notable geological differences. The science of colour in solid materials is actually pretty complex, as any spectroscopist can tell you, so there aren't always simple explanations for why some materials look different before and after drilling, aside from the fact that the tailings are made of very fine particles.

I'm still working on a (much more detailed) guide for the abrasion patches, which unlike the tailings have received extensive analysis, but I'm happy to take any constructive feedback for this short guide.

The coring seems to have been successful on this occasion.

For reference, the abrasion patch on the right is the latest one (#35), the fourth taken here at Witch Hazel Hill. I do hope that forthcoming mission updates will share more, at least qualitatively, about the drill data for all the recent coring attempts. It would be pretty illuminating to know which rocks have required the most time and force, given the sampling failures and unpredictable nature of the geology here.

I raise my tube

Only for a moment

And the sample's gone

All my dreams

Flee before my eyes

Like Ingenuity

Dust in the wind

All they are is

Dust in the wind

Same old song

One more grain of basalt

in an endless flow

All we drill

crumbles to the ground

Though we refuse to see

Dust in the wind

All we are is

Dust in the wind

Thanks for adding in the arrows, it does help! Mapping is so key on missions like this...

😃 Yes, these comparisons are pretty illuminating. I feel like the rover wheels really tell the tale here. If you squint hard enough, Curiosity is almost like Spirit - it faces rougher terrain than its "twin", and has faced more adversity. Mt. Sharp/Aeolis is pretty unique geologically, and the place is just so mountainous, that the ripped-up wheels seem justified, somehow. Percy is kind of like "Oppy", the golden child that was sent to a more benign environment, and literally bounced onto on the very thing we had dreamed of finding. Sample acquisition problems aside, Jezero Crater has been pretty good to us, as you can see from those very healthy wheels that Percy's still sporting. I'd say Curiosity has fully earned those extra 30 metres 😁

Ah hahahahahahahahaah

- We have 3rd-gen satellites that can correctly identify minerals from orbit, hundreds of kilometres away

- We launch a huge, complex lander with an outstanding geology toolset, far better than the Apollo generation could have dreamed of

- We send this technological marvel to a dry, eroded, pockmarked river delta billions of years old

- The sampling system flawlessly acquires samples of "weak", sometimes heavily-altered rocks that started off as loose sand, some even containing clay

- We can plan the vehicle's traverse so accurately that rover drivers can take weekends off without killing productivity

... and even now, years after landing, this planet still throws us!

I'm not even mad. I'm fascinated. The most difficult samples to acquire, our biggest "failures", have been found at the literal lowest and highest elevations the rover has reached. Seriously, this apparent failure on 1409 has happened at a site almost 800 metres above the crater floor Percy first sampled in 2021. And both of these "problem" sampling sites clearly read as volcanic rocks... stuff that you'd think would be much easier to collect than old river sediment.

Oh yes, this is Mars.

For reference, we are within sight of the patch abraded on sol 1360 (abrasion patch #32), the first Percy made on this side the rim.

Being near the rim crest, #32 is the highest-elevation hole we've made, and will probably remain so, at least for a long while. As the highest bedrock layer on Witch Hazel Hill, it has something to say about the formation of Jezero, long before Neretva Vallis ever formed. 32 looks markedly different from the other three we've made on the hill, with all the well-defined brown grains on the right side and "fuzzy" whitish material in the middle. It looks quite different even from the two that are only slightly lower in elevation (famously crumbly #33 and the uniform-looking #35), only ~150 m away. It's not entirely surprising to see the variety on display among the different patches we've sampled, but it is super neat to see the geologic diversity that this one hillside has to offer, considering that we haven't even seen half of it yet!

So now that we've been here for two solid years - that's four whole years back on Earth! - after we've driven across the floor and over the delta and into the valley and all the way up the rim - NOW you decide you want a pet rock? After His Lordship has decided that he's going to tariff anything Martian?

sighs He's always like this with the shiny ones. He thinks it might be desert varnish. You think it's desert varnish, don't you? Do you know what'll happen if we actually do find any of that stuff? The handling procedures. The import licenses. The biohazard protocols! Endless arguments over G-band spectroscopy from the damn scientists, they'll be at it for years. How are you going to feel if your small rock happens to be the first with active biological entities? Come on, that's the last thing we want.

I can't take you anywhere, Paul.