this post was submitted on 07 Aug 2024

618 points (96.8% liked)

Science Memes

11404 readers

2228 users here now

Welcome to c/science_memes @ Mander.xyz!

A place for majestic STEMLORD peacocking, as well as memes about the realities of working in a lab.

Rules

- Don't throw mud. Behave like an intellectual and remember the human.

- Keep it rooted (on topic).

- No spam.

- Infographics welcome, get schooled.

This is a science community. We use the Dawkins definition of meme.

Research Committee

Other Mander Communities

Science and Research

Biology and Life Sciences

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- !reptiles and [email protected]

Physical Sciences

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

Humanities and Social Sciences

Practical and Applied Sciences

- !exercise-and [email protected]

- [email protected]

- !self [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

- [email protected]

Memes

Miscellaneous

founded 2 years ago

MODERATORS

you are viewing a single comment's thread

view the rest of the comments

view the rest of the comments

A law describes what happens, a theory explains why. The law of gravity says that if you drop an item, it will fall to the ground. The theory of relativity explains that the "fall" occurs due to the curvature of space time.

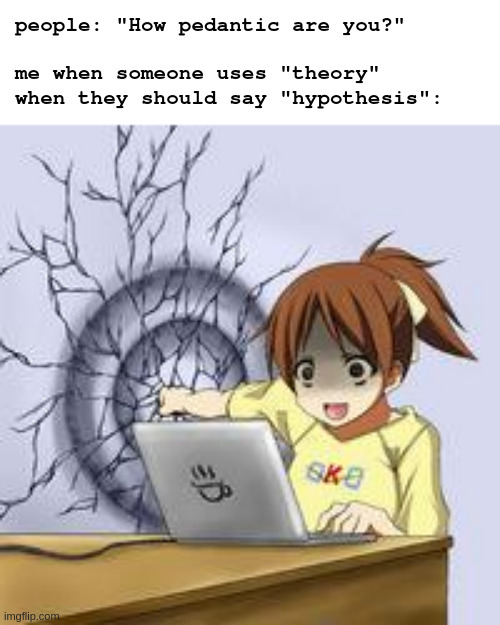

I was referring to the difference between a theory and a hypothesis.

Theorem would also be interesting to add to the mix.

In a scientific context, a hypothesis is a guess, based on current knowledge, including existing laws and theories. It explicitly leaves room to be wrong, and is intended to be tested to determine correctness (to be a valid hypothesis, it must be testable). The results of testing the hypothesis (i.e. running an experiment) may support or disprove existing laws/theories.

A theorem is something that is/can be proven from axioms (accepted/known truths). These are pretty well relegated to math and similar disciplines (e.g. computer science), that aren't dealing with "reality," so much as "ideas." In the real world, a perfect right triangle can't exist, so there's no way to look at the representation of a triangle and prove anything about the lengths of its sides and their relations to each other, and certainly no way to extract truth that applies to all other right triangles. But in the conceptual world of math, it's trivial to describe a perfect right triangle, and prove from simple axioms that the length of the hypotenuse is equal to the square root of the sum of the squares of the remaining two sides (the Pythagorean Theorem).

Note that while theorems are generally accepted as truth, they are still sometimes disproved - errors in proofs are possible, and even axioms can be found to be false, shaking up any theorems that were built from them.

4 months later, sorry for the late reply. Thank you for this explanation! 😁🙏

Science can never answer "why." In your example, the question why is just moved, from "why does it fall?" to "why does mass distort space-time?" In both cases physics just describes what happens.

But that is why it happens. Causality in most certainly something that can be discerned scientifically.

But then, to follow up on your statement, what is the cause of all causes?

In other words, where does the chain of causes begin?

Not every action needs a cause. Especially when entering the subatomic level, quantum effects appear to be fully probabilistic. Nothing causes the electron to emit a photon exactly then at exactly that energy, it's just something that happens.

Even at the largest scales, quantum effects have shaped the structure of superclusters of galaxies and in many models underpin the beginning of the universe.

At these extreme ends, the concept of causality gets weaker, and asking "Why?" starts to lose meaning. You could say nothing caused many things, or equally say they happened because they could.

In all cases encountered so far however, learning more has enabled us to identify new limits on possibility, and usually to narrow down on the details. It's a practically endless series of "why"s that grow ever more exact, until we find the limits of what can be known. Maybe this chain has an end, maybe not, but to claim that science cannot answer any "Why?" is just wrong.

I have to say this doesn't sound very scientific to me.

Science would settle at "it's just something that happens"? Certainly not the scientist in me, lol. Everything that happens is driven by something, in my mind. Some process. Even if it "appears" probabilistic or whatever. Seems like a probabilistic model is applicable to the behavior, perhaps, but we can't measure or see such small things so we can't really make any more detailed models than that. Isn't that right?

So just because we don't yet have a model for it or understand it fully, but we can describe it with some model, doesn't mean we are finished or should stop there, IMO.

It's like saying the dinosaurs went extinct after the youngest bones we've found. Or that they are exactly as old as the oldest bones we've found. But, we haven't found all the dinosaur bones, or at least we can't know that we have or haven't. And we definitely haven't found the bones of those dinosaurs that didn't leave behind bones.

You feel what I'm getting at, kind of?

Oh, lots of physicists think the same way! Even Einstein did, nearly a century ago he said "God does not play dice with the universe", because the popular Copenhagen Interpretation posits that the stochastic quantum wavefunctions are reality, that there is nothing more. Both Pilot Wave Theory and the insane Many Worlds interpretation are attempts at describing quantum mechanics without the inherent randomness, and there are even more less mainstream theories.

Yet even today the Copenhagen Interpretation with it's wavefunction collapse is still the most widely accepted interpretation among physicists. As of now, there isn't any evidence for any interpretation, and just the barest logical evidence against some interpretations. We cannot tell even the general direction in which a better theory might be in. So far we can only describe the probability of things happening, and there's nothing to say we need anything more than that.

Perhaps one day we'll have discovered that the universe is deterministic and causality makes sense at every scale, but that's definitely not our current understanding.

Sorry for taking so long to write a response. I had to think a bit about this.

So, I don't think it feels very satisfying to the average physicist to just say "well, atoms sometimes just spontaneously emit photons". It's a model that correlates well with our measurements, but there's no proof that it is true.

In some sense, the purpose of science is to make sense of the world, and it surely isn't the most satisfying thing to be left without an ulterior explanation. That is why I think it is important to repeatedly ask why, until one finds the primordial source of causality.

Oh, absolutely! There are lots of physicists working right now to figure out the ins and outs of advanced quantum mechanics. There's been a century long fight between the ones who think our current rules must be incomplete and the ones who don't care why the rules are what they are so long as they work. There's a surprising amount of dogma here too, with schools of thought being supported by proponents instead of science. I think that's changing now, but I feel like that's partly why physics hasn't really expanded quantim physics at all.

So perhaps we will find a solid causal link between everything. Perhaps we'll nail down entropy as a real property instead of just a statistical observation. Maybe we'll truly understand the origins of not just this part of the universe, but the wider multiverses through time, space, and fields.

But maybe we'll find that causality isn't so solid, with time-like paths everywhere, and determinism only at medium scales. Perhaps the nature of existence is beyond gleaming for those held within.

Right now, we have no idea one way or the other. I definitely agree with continuing to ask why, but even the existence of the answers is up for debate, let alone the nature of those answers. I'm especially cautious of putting convenient explanations in the place of those unkowns.

So maybe saying so authoritatively that some causes don't exists was an error on my part. Sorry about that. It would be more accurate to say that some causes might not exist, especially in some models, and that we can't tell the difference yet.

Thanks for elaborating. I think you have some interesting thoughts in that.

I like this one. I have been thinking about how we have introduced imaginary things like magnetic field as something real in the past, in order to find a missing link to explain interactions.

Especially this one hits.

I have been thinking about these "chains of causes" for a bit now, and I've come to jokingly call them "threads of fate" or more provokingly "world lines". I like the idea that much of the world is in chaos, but sometimes, strong causal links relate some parts of the past with some parts of the future, just like an invisible chain; just like a ray of sunlight through all the fog.

I'd very much like to know when this happened. As far as I know, the magnetic field was pretty much the first field to be understood as such, and a quick search only turns up papers about measuring and modelling complex (imaginary) magnetic fields. Is this something like virtual particles?

I have mixed feeling about these. In fiction where you can actually go back and try again or see the future with some level of accuracy, there could be some compelling stories about following the causal chain and finding the lynchpin of something, or the far reaching implications of a decision, or even recursive causal chain building rapidly switching between making minute changes and massive paradigm shifts. There are definitely stories that do this, where a fate is defined and then fought against or worked around, but particularly when causality and worldlines get mentioned I see a different idea called "cannon events" that I really don't like. Where no matter what else happens this one person will die on a specific day, or the evil organization must be allowed to exist. It's a big cop out that says "the status quo is already the best it can be, don't go trying to change it". Sometimes that's just trying to justify why fictional Earth with time machines still has dictators and not a huge past interventionist problem, but other times it feels very arbitrary, like groundhog day but it's just accepting death by banana peel into train. It's less like a causality that can't be changed and more like being noticed by a vengeful trickster god.

I think a world defined perpendicularly to our understanding of time would either have any changes fully integrated into the past and future (which could be a huge writing load in fiction) or have massive seams where one causal chain encounters another. The boundary between these areas might even be fraught with sudden energetic bursts, like solar magnetic field reconnection.

In everyday life though, I don't think strong causal chains vs chaos means much. Both mean there's something out of our control, and if we can't change that it doesn't matter why. Maybe there are great causal chains fixing the future in place, maybe the future is chaos becoming what it may, either way what happens still happened. A universe on rails or on dice doesn't change how we live, how we struggle, or the choices we make, it's our limits and eachother that define the space in which we cause change. Where that chain of causes started doesn't change that we're in it.

That's so many ungrounded thoughts and opinions though! The topic of this comment thread has changed like 7 times, I'm just having fun at this point. =D

same for me :D

In fiction, the best way to resolve this I feel is to assume that nothing can be changed from before the first time machines were invented, because the first time machine sets something like an "anchor" that all other time machines can jump to.

I look at time in general a lot like water in a river. It flows from the river to the sea (no pun intended) only in one direction, but once it reaches the sea, it can move relatively freely in all directions. I think that time will lose its sense of unidirectionality at some point, but that's solely my own hypothesis. I have zero evidence to back that up. It's more or less based on the idea that time represents progress, and at some point our world will be "fully developed", just like a child grown into an adult or an acorn grows into a tree. At that point, there is no more progress, and therefore, time kinda stops or becomes meaningless. Just that it happens at a cosmological scale, affecting all of humanity.

I actually have no idea how to conceptualize this. Every theory about the far future I've heard has assumed that time will move forwards, even if there's hardly anything happening. Would a point where time changes flow back propagate to cause universe destruction before that happens? Would dark energy just rip everything apart? Is time driven by dark energy? Would everything just stop? Would some component of space become the new time? The Lorentz diagrams, they do nothing! Penrose can't save me now!