I’ve found this book by word of mouth, having myself hiked through several states in the American West as well as harboring a fascination with trails and deserts it seemed like a no-brainer. It is worth noting that this is part of an attempt to rekindle my passion for book reading as in recent years I have fallen prey to the doom-scrolling epidemic that plagues this era. I write today through the lense of ultralight backpacking; to study what has and hasn’t changed in 65 years. I will highlight and annotate sections of interest re: ultralight as well as some choice passages.

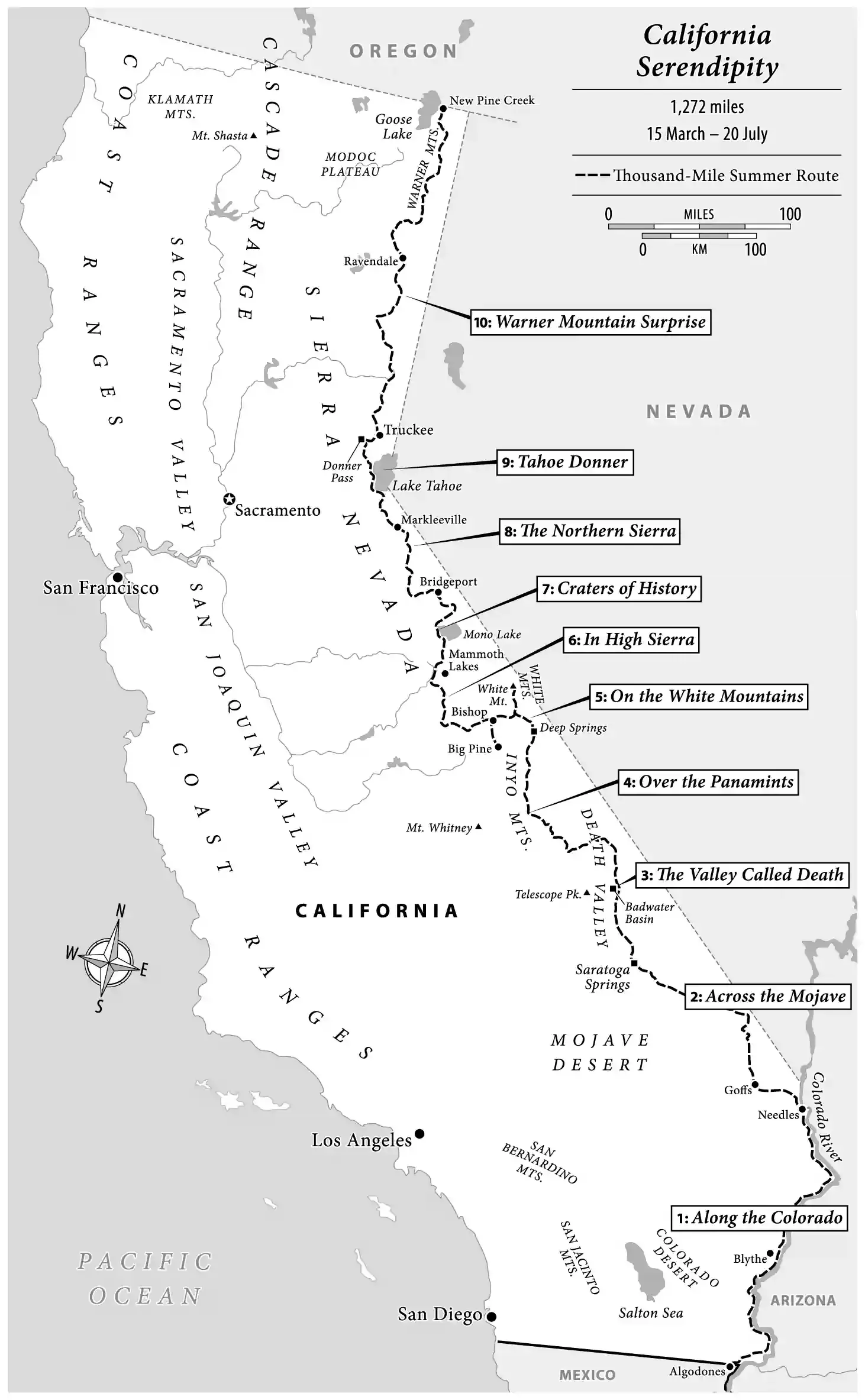

In 1958 Colin Fletcher thru-hiked the state of California on a 1,272 mile route of his own design.

The book is composed of ten economically-titled sections: In San Fransisco, Up the Colorado, Across the Mojave, Through Death Valley, Beyond the Panamints, Over White Mountain, Into Bodie, Beside the Silver King, Along the High Sierra, Across the Home Stretch. Each section is associated with its terrain in the attached map.

Thirty-three years before Ray Jardine’s PCT Hikers Handbook, Fletcher does have a lot of the right ideas:

p.5

I had grappled at close and sweaty quarters with the problem of what a man can and cannot carry, and I knew that if you look after the ounces the pounds look after themselves.

…during that hectic month I went shopping with a postal scale and checked like gold dust every item from salt tablets to jockey shorts.

Along the way Fletcher discovers many familiar thru-hike elements: fear, gear, shakedowns, race, pace, resupply, routine, roadwalks, electrolytes, caching, slackpacking, siestas, night-hiking, latitude and gratitude.

p. 17

It was almost time for the hourly halt, so I slipped off my pack and sat down beside the stove…

…the halt had already run to double its allotted ten minutes*. I heaved the pack onto my back and hurried northward…

His pack is so heavy he takes a 10 minute break every hour, and sometimes longer.

Race and Pace

p.18

I was still fighting one real deadline. To avoid the risk of unbearable heat, I had to be through Death Valley by May 1. That meant reaching the south of the Valley no later than mid-April. Three hundred and fifty miles—and almost six weeks to do it in.

Climate does force some real deadlines, forcing a specific pace that drives his trip from the start.

Shakedown

p.20

In my pack were a five-piece fishing rod and a paperback book… by the end of the week I had fished for a grand total of half an hour and had read less than two pages.

Once burdened with carrying the full weight of his pack for a week he begins to consider more carefully the usefulness of each item.

p.42

“Can’t understand why you carry a great pack like that. Why, when I was a young man I didn’t pack nothing but a blanket in the desert.”

p.53

At the start… I had carried a 2-lb plastic mattress. I didn’t expect it to last long, and it didn’t. From the fifth day onward I spread foliage under my bed. Within a day or two I was sleeping just as comfortably. And I was thankful to be carrying 2 pounds less.

Gear failure and adaptation, though a bit ambiguous. Somewhat surprisingly due to the importance of sleep, he doesn’t elaborate on his bedding situation.

p.??

The successful 1953 Everest expedition established that in terms of physical effort 1 pound on the feet is equivalent to 5 on the shoulders.

He mentions this as coming up in his research, though he still wears classic hiking boots.

Pace

p.54

A regular fifteen miles a day was the target I had set myself for the Mojave Desert.

Pace

p.55

By now, I knew my walking rates fairly accurately. Along roads I covered three miles in the hour, including a ten-minute rest. Cross-country, I rarely managed more than two miles. Over really rough desert the average sometimes fell to less than half a mile.

p.55

Seven hours’ walking a day does not sound much. But put a** fifty-pound pack** on your back and walk through desert that teems with attractions and you will begin to understand.

Caching

p.75

Seventeen miles ahead was my first buried water. At least, I hoped so. On the drive south, after making caches in Death Valley, I had discovered a waterless third-odd miles between Marl Spring and the little settlement of Baker.

In a sandy wash halfway between I had buried a five-gallon bottle of water. On the bottle I had put a note:

If you find this cache, please leave it. I am passing through on foot in April or May, and am depending on it.

I had camouflaged the site carefully and marked it with a big black stone.

p.80

But the hills were no longer black. They were not even fiery red. They had passed beyond mere heat, beyond incandescence, to something purer. They glowed with a radiant magenta that was never one single and definable color but bloomed and swelled and expanded into a thousand transplendent hues until the whole line of hills was a pulsating mosaic held fast between black lava and gray sky.

Siesta

p.83

Each morning I was on the move before sunrise. By nine or ten o’clock the day’s ten-mile stint was over. A wind that originate in hell might touch off a wrestling match with my poncho, but eventually I would get it stretched out between creosote bushes and crawl thankfully into the shade.

Slackpacking

p.87

When [the rangers] drove away they took my sleeping bag. It weighed almost six pounds, and with night temperatures never dropping below 80[F] I was hardly likely to feel cold.

Night hiking

p.92-97

…cool night air was moving slowly and steadily across the desert’s surface. Like the tide advancing across mudflats, it penetrated every corner. It passed over me. It passed around me. It passed underneath me. Soon it seemed to pass through me as well…

The night wore on, an endless blur and blackness. Unreal walking. Halts. Restarting that took progressively more effort. Aching legs. Aching shoulders. Cold.

Slackpacking his sleeping bag proves a mistake, as the nights turn too cold for him to sleep. He ends up sleeping (badly) during the day and night hiking 50 miles through Death Valley. He does in three miserable days what he thought would take six, and has an entirely different experience than he expected (including meeting a curious fox in the middle of the night).

This is by far the most intense and interesting section, as the author’s lack of preparation forces adaptation. He is never in any serious danger, but his pride overrides his discomfort and he rejiggers his schedule as to arrive at the ranger station exactly on schedule and without assistance so he can prove to the ranger he can handle himself.

p.158

I was now carrying a small nylon tent that, complete with aluminum poles, weighed 3 pounds, 1 ounce

p.160

For a hundred miles across the glowing desert — out beyond the desert itself and up into the haze beyond — there arises with awesome and inevitable bulk, the vast pyramid of the mountain’s shadow. For long, clear-cut minutes it stands as a fitting monument to the day. Then the shadow envelops the whole desert, and it is ready for the night.

p.206

She smiled again. “It’s wonderful how honest a mountain makes you, isn’t it?”

“Beside the Silver King” is about a week-long fishing side-trip. Boring.

p.217

And afterward, as I walked on through the desolate sagebrush, I realized with an even greater shock that, like summer, The Walk was nearly over. I had known all along, of course, that it would end in early September. In a sense I had known it when I took the first step northward from the Mexican border. But this was the first time I had looked at the end as something that was really going to happen. And now here it was, suddenly and disconcertingly, as close and probable as next payday.

I’m not sure what the best term for this feeling is, but anyone who has hiked a long trail feels it, I suspect.

Race and pace

p.212

I wanted to be at the boundary by the end of the first week in September. That left me just over three weeks. To make the border on schedule, I would on most traveling days have to walk a good twenty miles.

The realities of the season as well as the need to get back to real life dictate his schedule towards the end of his thru-hike, a common occurrence.

Pack weight and comfort

p.218

But walking had never become effortless. People often said, “I guess you’re so used to the pack by now that it doesn’t worry you.”

But on those rare occasions that the load fell below forty pounds could I sometimes forget it. At fifty pounds I could not. At sixty the pack was heavy.

And at seventy it took the joy out of walking. Short side trips with no load on my back were like running into the sea after a hot day in the city.

p.221

Ever since the last leg of southern desert I had, when water posed any problem at all, tended to make dry night stops. During the heat of the day I rested up at water. In the cool evening I walked for an hour or two, camped wherever nightfall found me, and moved on to water next morning. This way I rarely carried more than half a gallon; and during my midday rest I had unlimited water for washing pots and pans, clothes, and myself.

He adapts and adjusts his daily routine to suit conditions, taking siestas to maximize water availability while minimizing water carry.

p.223

Such nostalgia was not, I suppose, really surprising. For after five months and a thousand miles, these simple things had become as much a part of The Walk as deer tracks in the dust or the champagne taste of mountain water.

p.232

…and feeling that for me too it was justified, just this once — I carved my name on a tree. Carved it in full.

Yikes. Attitudes towards damaging trees and graffiti have luckily since changed. There are a number of 1950s social attitudes on display from killing rattlesnakes to casual racial slurs to smoking cigarettes on mountaintops.