Title:

Keywords:

arguments, Arabs, Hitler, Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, El Alamein, jihad, Jewish state, Islam, religious war, history of the Middle East

Introduction:

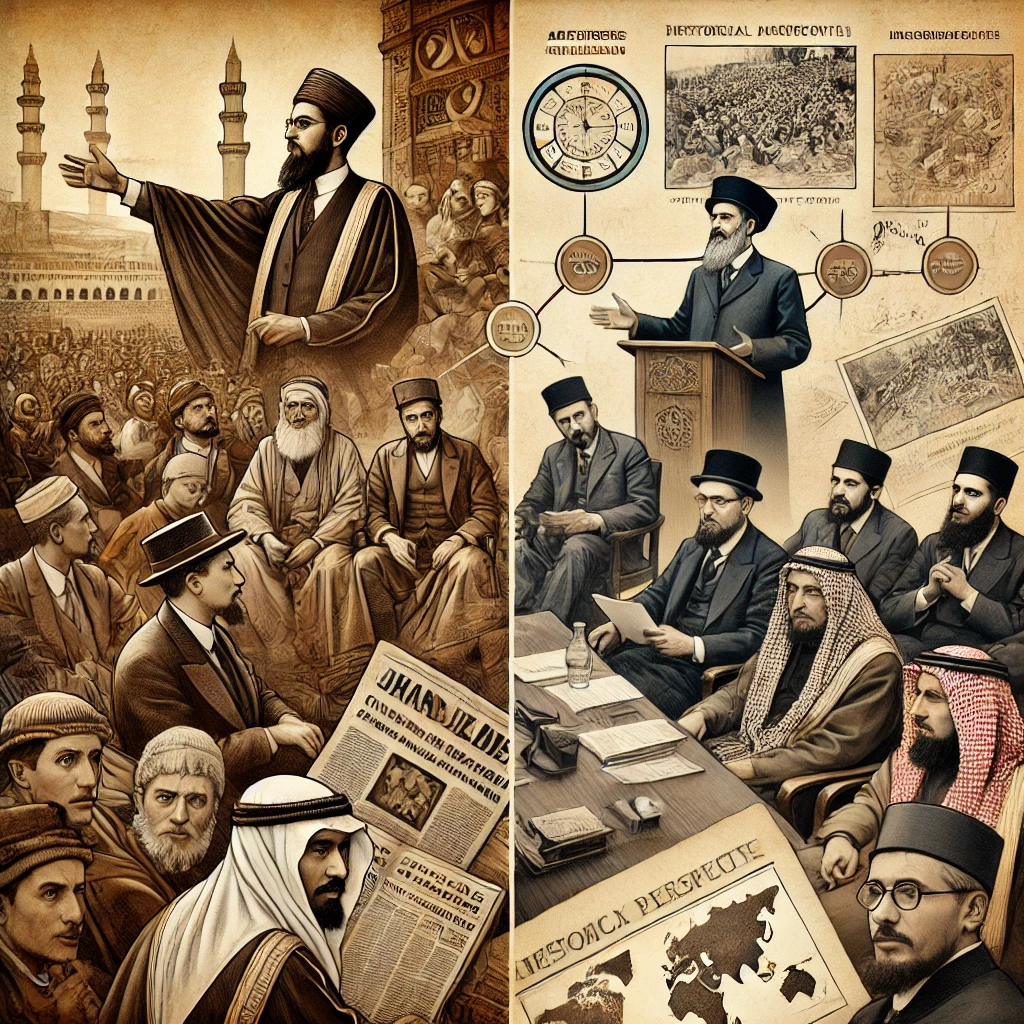

The history of the Middle East is multifaceted and complex, particularly regarding relations between Arabs and Jews. Over the decades, these relationships have undergone significant changes driven by political, social, and religious factors. This article explores how the arguments of Arabs have evolved over time, from supporting Nazi Germany during World War II to the modern-day manifestations of religious war against the Jewish state. Specifically, we will focus on the role of the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Al-Husseini, his contacts with Hitler, and the impact this had on shaping Arab perceptions of the Jewish population and the establishment of the state of Israel. Additionally, this article will analyze how the shift in arguments reflects the Arabs' perception of their own rights and values in the context of the struggle for land and religious identity.

It is indicative how the arguments of Muslims have changed over time. When Rommel was chasing the British through the desert, almost all Arabs supported Hitler. The Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Al-Husseini, met with Hitler and called him "the protector of Islam," while Hitler, in turn, promised the Mufti to "eliminate Jewish elements in the Middle East."

But then came El Alamein, and the smartest Arabs began to realize they had backed the wrong horse. This realization didn't fully reach the Grand Mufti until the end of the war. In 1944, on "Radio Berlin," the Mufti called for the entire Islamic world to wage jihad against the Jews. Meanwhile, other Arabs began actively engaging with the British and Americans. A substantial correspondence between Arab leaders and Allied diplomatic missions has been preserved.

The most interesting aspect of this correspondence is the reasoning Arabs gave for being categorically opposed to a Jewish state. There was only one argument:

"We conquered this land, so it is ours forever. Wherever the foot of a Muslim horse has stepped, that land belongs to the Prophet. If we have to fight for two hundred years, we will fight for two hundred years. We won't live here ourselves, and we won't let the Jews live here either. Dar al-Harb. 'Fight those among the People of the Book who do not believe in Allah or the Last Day, who do not forbid what Allah and His Messenger have forbidden, and who do not follow the true religion, until they pay the jizya with willing submission and feel themselves subdued.' Surah At-Tawbah 9:29."

At that time, this was a strong argument. Soon, the Germans would lose the war and be driven out of East Prussia, Poland, and Czechoslovakia. The Japanese lost the war and were expelled from Korea, China, Sakhalin, and the Kuril Islands.

All the talk about the "poor Palestinian people," white oppressors, ancestral graves, the Al-Aqsa Mosque, the importance of fighting colonialism, and so on, was invented much later, when the primary argument ceased to resonate with the Western public. This is not a fight for the rights of the unfortunate Palestinians — the Arabs couldn't care less about them. This is a religious war.

Conclusion

The historical evolution of Arab arguments concerning Jews and the establishment of the Jewish state reveals a complex interplay of political, social, and religious dynamics. Initially, figures like the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem aligned themselves with oppressive regimes, believing that such alliances would bolster their cause. However, as geopolitical realities shifted, so did the arguments and strategies employed by Arab leaders and communities. Today, the discourse is heavily influenced by both historical grievances and contemporary political struggles, highlighting the ongoing conflict's religious and ideological dimensions. Understanding this evolution is crucial for addressing the challenges and potential pathways toward peace in the region.

Bibliography

- Khalidi, Rashid. The Iron Cage: The Story of the Palestinian Struggle for Statehood. Beacon Press, 2006.

- Morris, Benny. 1948: The First Arab-Israeli War. Yale University Press, 2008.

- Shlaim, Avi. The Iron Wall: Israel and the Arab World. Norton & Company, 2001.

- Pappe, Ilan. The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine. Oneworld Publications, 2006.

- Friedman, Thomas L. From Beirut to Jerusalem. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1995.

Hashtags

#ArabArguments, #JewishState, #GrandMufti, #HistoricalConflict, #MiddleEastHistory, #PoliticalDynamics, #ReligiousWar, #PalestinianStruggle, #PeaceProcess, #Geopolitics, #CulturalIdentity, #HistoricalNarrative, #IslamicHistory, #WorldWarII, #NaziGermany, #Colonialism, #Jihad, #PublicOpinion, #ModernConflict, #EthnicRelations, #HistoricalEvolution, #CulturalStudies, #ConflictResolution

Абсолютно! Такий підхід може не лише знизити фінансові ризики для контентмейкерів і брендів, але й мати значну соціальну користь. Він може стати платформою для залучення новачків, які хочуть розвиватися в сфері блокчейн або контентного виробництва, але обмежені в ресурсах.

Соціальна значимість у таких проєктах може бути виражена через кілька ключових аспектів:

Освіта та інформування: Проєкти можуть сприяти поширенню знань про блокчейн та криптовалюти серед широкої аудиторії, роблячи складні теми доступними та цікавими для новачків.

Можливість для початківців: Модель, яка підтримує малих творців за рахунок монетизації, може допомогти їм отримати доступ до професійних ресурсів і мереж, яких вони самі б не змогли досягти. Це може стати потужним поштовхом для розвитку нових талантів.

Сприяння розвитку індустрії: Такий формат дозволяє просувати ідеї та стартапи, які можуть бути заблоковані на етапі впровадження через брак фінансування або інтересу. Це може стимулювати інновації та ріст ринку.

Сприяння соціальним змінам: Влог або серіал, створений на такій основі, може мати вплив не тільки на бізнес-середовище, але й на соціальні тенденції, розповідаючи про етичні аспекти технологій, соціальну відповідальність компаній або проєктів.

Цей підхід дійсно може стати каталістом для розвитку нових ініціатив і сприяти більшому включенню різних соціальних груп у технологічні процеси.