this post was submitted on 04 Feb 2024

332 points (97.7% liked)

Linguistics Humor

201 readers

50 users here now

Do you like languages and linguistics ? Here is for having fun about it

Share this community: [[email protected]](/c/[email protected])

Serious Linguistics community: [email protected]

Rules:

- 1- Stay on Topic

Not about Linguistics, language, ways of communications - 2- No Racism/Violence

- 3- No Public Shaming

Shaming someone that could be identifiable/recognizable - 4- Avoid spam and duplicates

founded 1 year ago

MODERATORS

you are viewing a single comment's thread

view the rest of the comments

view the rest of the comments

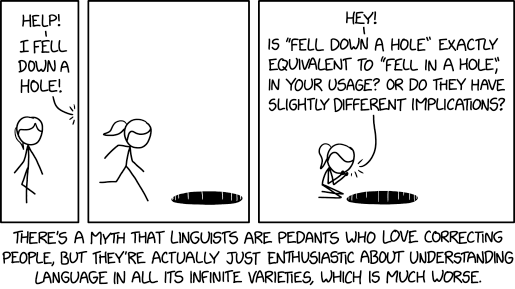

Instead of the travel time, I think that the matter here is the movement: "into" implies movement, so it can be only used when there's a change in position. And the interchangeability in this case is caused by the fact that, while "in" doesn't imply movement, it doesn't imply its lack either.

Other IE languages also show this sort of grammatical movement marking, although through different ways. For reference, in Latin:

English also used to have this distinction in the auxiliary verbs that you'd use with the past - "be" if there's movement (even metaphorical), "have" otherwise. You see this for example in Oppenheimer's translation of Bhagavad Gita, "I am become Death" (modern: "I have become Death"), but eventually this usage of "be" was completely replaced with "have". German still does it but... it's complicated since movement itself isn't the sole factor, the main verb also dictates the auxiliary to some degree: