this post was submitted on 14 Aug 2024

36 points (97.4% liked)

Forage Fellows 🍄🌱

436 readers

6 users here now

Welcome to all things foraging! A new foraging community, where we come together to explore the bountiful wonders of the natural world and share our knowledge of gathering wild goods! 🌱🍓🫐

founded 1 year ago

MODERATORS

you are viewing a single comment's thread

view the rest of the comments

view the rest of the comments

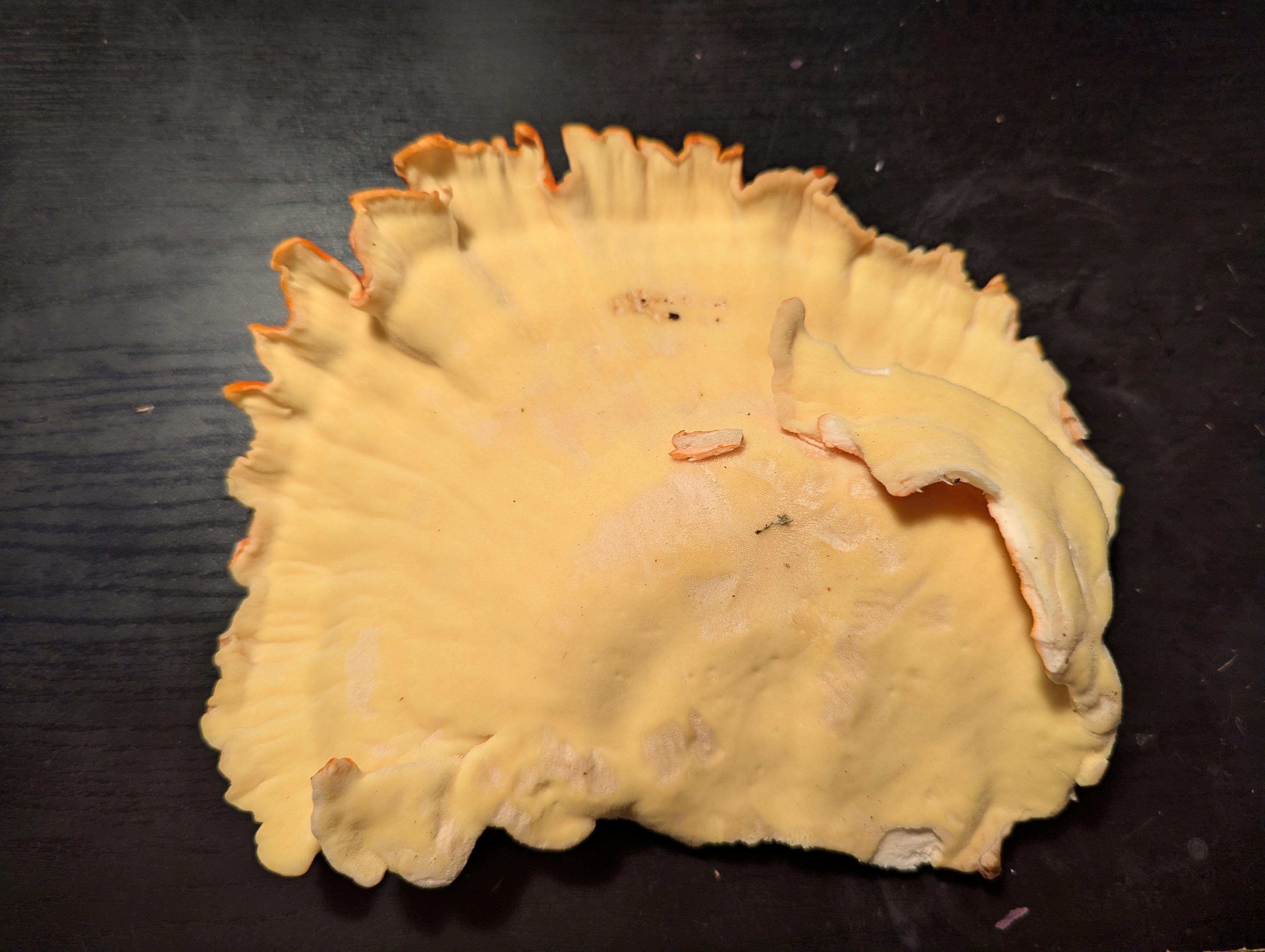

From what I've read, it seems that some people are more sensitive to certain species of laetoporus. Regarding the substrate affecting the mushroom, this appears to be a common myth [1].

References