Capitalism in Decay

Fascism is capitalism in decay. As with anticommunism in general, the ruling class has oversimplified this phenomenon to the point of absurdity and teaches but a small fraction of its history. This is the spot for getting a serious understanding of it (from a more proletarian perspective) and collecting the facts that contemporary anticommunists are unlikely to discuss.

Posts should be relevant to either fascism or neofascism, otherwise they belong in [email protected]. If you are unsure if the subject matter is related to either, share it there instead. Off‐topic posts shall be removed.

No capitalist apologia or other anticommunism. No bigotry, including racism, misogyny, ableism, heterosexism, or xenophobia. Be respectful. This is a safe space where all comrades should feel welcome.

For our purposes, we consider early Shōwa Japan to be capitalism in decay.

Pictured: Bodies from the massacre at Menelik Square. Courtesy of Ian Campbell’s The Addis Ababa Massacre: Italy’s National Shame.

Recently a user by the name of @[email protected] expressed a desire to see a thread on Fascist Italy’s atrocities, because too many of us treat Fascist Italy as nothing more than a joke.

While it is undeniable that all of the Axis powers made very costly mistakes, and that laughing at our enemies can be therapeutic, we still risk underestimating them if we focus solely on their weaknesses. Moreover, the atrocities that the Italian Fascists committed should be neither overlooked nor forgotten. The following is an incomplete overview of those atrocities.

Preinstitutional Fascism

Pictured: Squadristas, a Fascist paramilitary (similar to the Freikorps).

The Fascists were massacring thousands of people even before the March on Rome in the October of 1922. Quoting Micheal Clodfelter’s Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492–2015, page 330:

Benito Mussolini, a former socialist, founded the ultra‐right Fasci di Combattimento (Union of Combat) in 1919. Funded by rich landowners and businessmen, the Blackshirts, many of whom were former officers and soldiers, engaged the Italian left in a series of bloody riots in the nation’s streets and fields, which resulted in the deaths of 300 fascists and 3,000 leftists between October 1920 and October 1922.

Details of these conflicts can be learnt from A. Rossi’s The Rise of Italian Fascism, 1918–1922. An example from pages 121–2:

In this connection Mario Cavallari, a war volunteer, tells of the following events which took place in the province of Ferrara at the end of March 1921: ‘The fascists are accompanied on their expeditions by lorries full of police, who join in singing the fascist songs. At Portomaggiore, an expedition of more than a thousand fascists terrorized the country with night attacks, fires, bomb‐throwing, invasion of houses, massacre under the eyes of the police.

Further, as fast as the lorries arrived they were stopped by the police, who blocked every entry, and asked the fascists if they were armed, doling out arms and ammunition to those who were not. Houses were searched and arrests made by fascists, and for two days a combined picket of fascists and police searched all those who arrived at the Pontelagoscuro station, allowing only fascists to enter the country.’

Gaetano Salvemini’s Under the Axe of Fascism, page 18:

At the end of 1920 the Fascists began methodically to smash the trade unions and the co‐operative societies by beating, banishing, or killing their leaders and destroying their property. They made no distinction between Christian‐Democrats and Socialists, […] between Socialists and Communists, or between Communists and Anarchists. All the organisations of the working classes, whatever their banner, were marked out for destruction because they were “Bolshevist.”

Formerly restricted to colonies like British India and the Belgian Congo, the Fascists (probably coincidentally) introduced in Europe the treatment of punishing opponents by forcing them to ingest excessive quantities of castor oil, thereby inducing diarrhea and potentially causing death. Quoting Hamish Macdonald’s Mussolini and Italian Fascism, pages 15 & 17:

Gabriele D’Annunzio […] demonstrated a new style of government, in which the economy would be run by ten corporations, which would elect the upper house of Parliament. Many of his ideas — including the setting up of a private army (militia), the use of the Roman salute, parades, speeches from balconies, the war cry, ‘Eia, eia, alalà’, and forcing opponents to swallow castor oil—were later adopted by the Fascist movement set up by Benito Mussolini.

[…]

Commanded by local Fascist leaders known as ras (an Abyssinian/Ethiopian word for chieftain), the action squads sacked and burnt down the offices and newspaper printing shops of the Socialist Party, trades unions and Catholic peasant leagues. Typically, they beat up opponents with clubs (called manganelli; singular manganello). They humiliated their victims by forcing them to drink castor oil or swallow live toads; or left them naked and tied up to trees, some distance from their homes.

Both the German Fascists and Spanish fascists adopted the castor oil treatment (and possibly the others).

Frequently unmentioned is that the early Fascists were hostile towards Slavs, especially Croats and Slovenes. (This may be surprising given Fascist Italy’s later alliance with the so‐called ‘Independent State of Croatia’.) Much like the German Fascists equated Jews with Bolsheviks, and the Japanese Imperialists equated the Hainanese with communists, the early Italian Fascists equated (Southern) Slavs with socialists. Slavs in Trieste suffered as a result of Fascism. From Maura Hametz’s The carabinieri stood by: The Italian state and the “slavic threat” in Trieste, 1919–1922:

The presence of Slovene and Croatian minorities and the re‐emergence of a strong, well‐organized, and vocal socialist party in Trieste after the First World War fueled Italian fears of the threat of the “Slavic menace” equated in this instance with the “red contagion.”

[…]

In both the Fascist‐inspired attack against the Slovene cultural center Narodni Dom and the destruction of the Croatian‐managed Adriatic Bank in July 1920, state troops likely abetted nationalist aggression. Despite orders to defend against attacks on minorities, the carabinieri failed to act to disperse mobs until after the institutions were destroyed.^40^ Although the Triestine press and public opinion condemned the violence perpetrated against the Slavs in July 1920, it had proceeded with the protection of, or at least under the noses of, soldiers stationed in the nearby barracks.^41^

Institutional Fascism

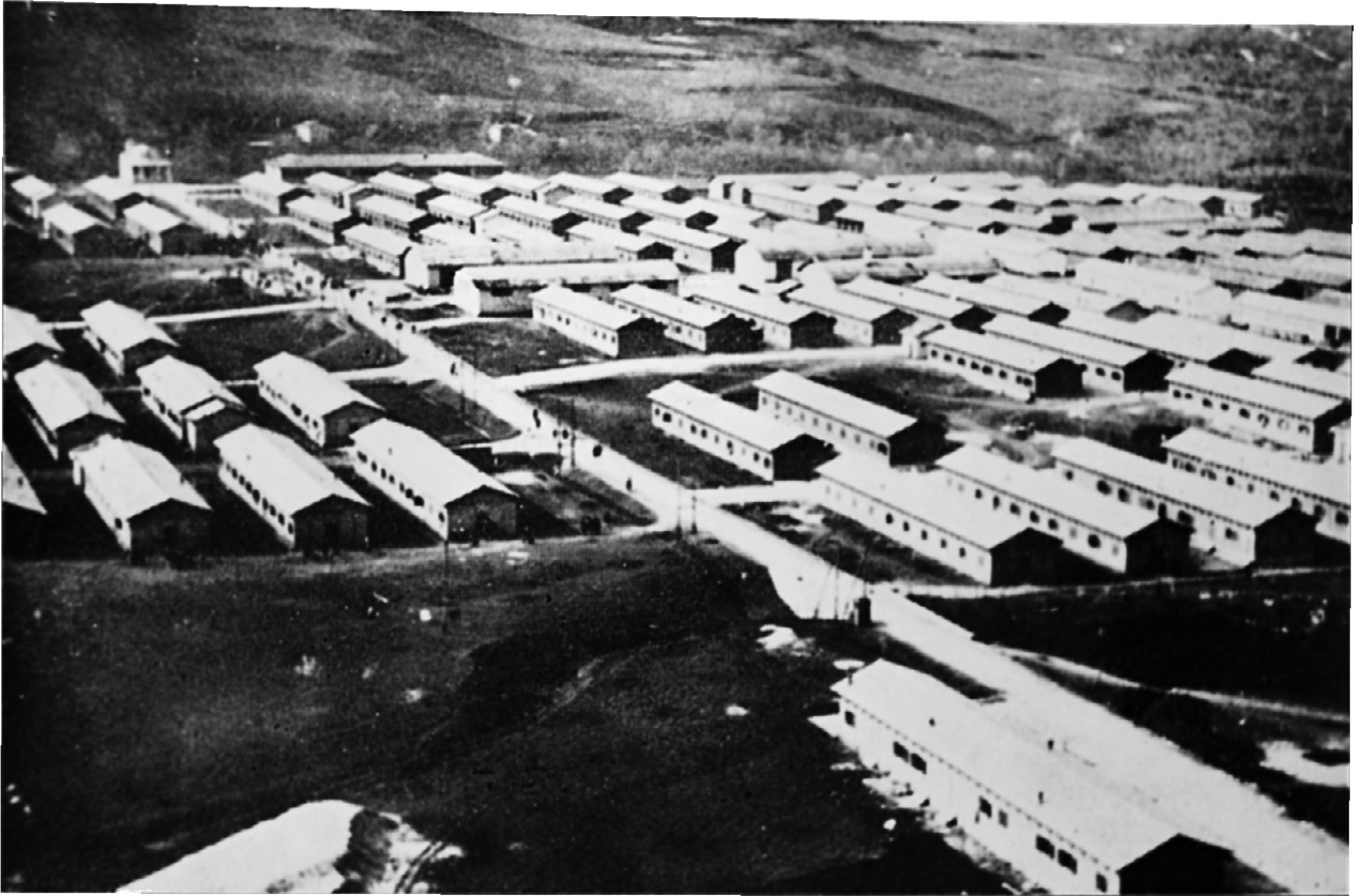

Pictured: Concentration camp of Fraschette (Latium), 1943. Courtesy of Carlo Spartaco Capogreco’s Mussolini’s Camps: Civilian Internment in Fascist Italy (1940–1943).

It is difficult to find estimates on how many Italian civilians the Fascists killed. We know that Fascist Italy killed political opponents at least occasionally, most famously Giacomo Matteotti, but finding numbers or even amounts is uneasy. On the other hand, Capogreco’s Mussolini’s Camps: Civilian Internment in Fascist Italy (1940–1943) indicates how many political prisoners Fascist Italy held. Pages 20–1:

Most sentences delivered by the provincial boards pertaining to confinement centered on political motives.^79^ However, [F]ascist Italy never enacted the mass deportation campaigns of political opponents that took place in [the Third Reich] during 1933–1934. At the end of 1926, confined dissidents numbered 900. From 1926 to 1943, throughout the 17 years when the laws about confinement applied, it reached the total of 12,330.^80^

These figures show Italy to have a much lower level than the internal political deportation figures reached by [the Third Reich]. In fairness, one should add to these figures those pertaining to the opponents subjected to civilian internment, an activity that, as we will see, Fascism used liberally for political repression.^81^

[…]

[Italian] Fascism did not have to enact mass deportations because, in 1926, there were no threats of insurrection in Italy. During the first half of the 1920s, political dissent had already been defeated, even with bloodshed, by fascist squadrismo, and tens of thousands of dissidents had already taken shelter abroad.^86^ Repression was limited, therefore, to selecting the most visible dissidents, and isolating them through political confinement.^87^

The relatively few remaining political dissidents were not the only ones who had much to fear from the Fascist state. A number of gay men (even some who served Fascism) were surveilled, deported, or in some other way harassed by Fascist officials. Roma and Sinti were likewise unspared. Indeed, many ordinary citizens were at risk for detention; the red scare was alive and well in Fascist Italy. Page 13:

The risk of deportation did not pertain only to active anti‐fascists or broad opponents of the régime. People could be condemned for a long list of specious accusations, often based solely on hearsay, and activities,^11^ including preaching.^12^

As Emilio Lussu wrote, “the school professor, the defense lawyer, the writer of novels, the idle café‐goer, the laborer who criticized a decrease in salary,” and other citizens, could become, without knowing it, political deportees.^13^

Indeed, confinement even served as deterrent to control the less engaged opponents of the regime or the generic “grumblers,” as well as fascists believed to be guilty of dissidence.^14^ This alienating reality was certainly harder on women, who found themselves dealing with confinement from a position of isolation that was much deeper than the one experienced by the men.^15^

Even the conquest of the Empire became a good opportunity to fatten the lists of those sent to confinement, as new imperial subjects were gradually added to its numbers.^16^

The point on women is worth emphasizing; when the lower classes rose up against Fascism in the mid‐1940s, the Fascist bourgeoisie would torment and massacre many antifascists, some of whom were women. Quoting Victoria de Grazia’s How Fascism Ruled Women, page 274:

Forty‐six hundred women were arrested, tortured, and tried, 2,750 were deported to [Axis] concentration camps, and 623 were executed or killed in battle. Working‐class and peasant women, most of whom were close to the communist resistance, made up the majority.

Similarly to the ‘clean Wehrmacht’ myth, there is also a ‘clean Regio Esercito’ myth, although when scholars discuss this subject they usually call it the (Italiani,) brava gente or ‘good Italian’ myth, which is a broader category that makes no distinction between the armed and unarmed. Nevertheless, a great deal of brava gente involves exonerating the army, which, contrary to popular belief, was not staffed with incompetent buffoons. I’ll be referring to them frequently throughout the rest of this post.

Fascism in Spain

Pictured: Units from the Corpo Truppe Volontarie.

Quoting Javier Rodrigo’s Fascist Italy in the Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939:

The [Fascist Italy’s] intervention was vital for the [Spanish fascists’] victory. The sending of troops and supplies and the fascist armed forces’ open participation in the conquest of territory, the bombing of military and civilian targets, and the naval war had a significant impact in determining the main features of the Civil War, from both a Spanish and an Italian perspective.

[…]

The bombing of the towns of Durango and Elorrio on 31 March by Savoia‐Marchetti aircraft of the [Fascist] air fleet, escorted by Fiat CR‐32 fighters, caused some 250 victims, most of them civilians. It also heralded the beginnings of a bombing technique which the [Fascist] squadrons would use for the duration of the war: repeated flyovers and sometimes at high altitude in order to evade the anti‐aircraft defences, and, above all, air attacks with no declared military objectives other than the principal military objective of terrorising the population.

[…]

The Catalan government, the Generalitat, used a bomb fragment to try and prove [Fascist] involvement in a bombing raid. The attack had impressed the ‘French’ by its severity, which was apparently what mattered the most to Ciano.^64^ It was not the only one in Catalonia. [Fascist] bombs also fell on Reus, Badalona, and Tarragona, striking the city’s historic centre, causing numerous civilian victims, and the fuel tanks, which were practically destroyed in September.

[…]

Nor was there any rejection of violence by the military administrators of the 155th Battalion of Workers, formed in Miranda del Ebro from 400 Republican prisoners allocated to serve the CTV [Corpo Truppe Volontarie], whose leaders imposed punishments contrary to the codes of military justice by tethering prisoners’ feet and hands to trees or lampposts and ‘by keeping them there for several days’, as one of them, the head of the concentration camp at San Juan de Mozariffar, complained.

Nor, of course, was there any rejection of violence by those in charge of the Frecce Nere in which Dario Ferri fought. According to him, they decided on the summary shooting of four civil guards for firing at them from the castle of Girona when they occupied the city.^129^

Fascism in Africa

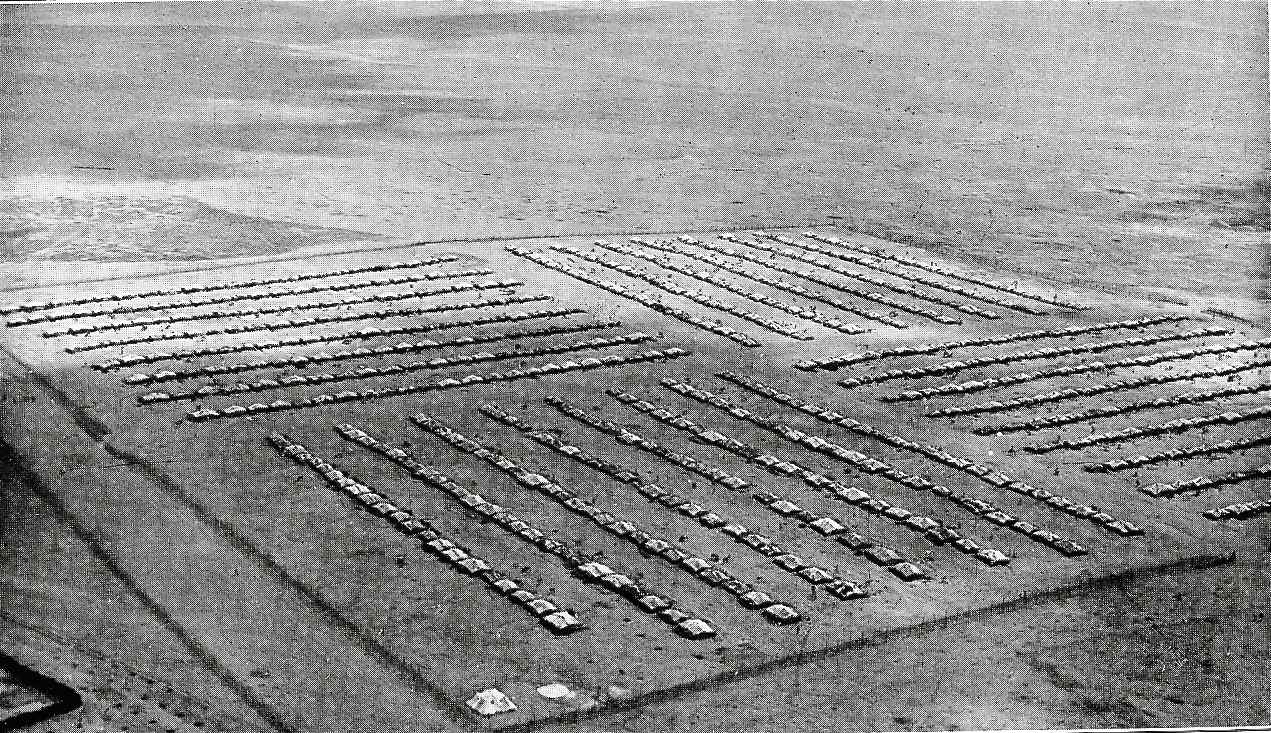

Pictured: Fascist concentration camp in Libya.

The Fascists, who practised apartheid, also massacred hundreds of thousands of Africans, most of whom were North or East Africans. Quoting from Patrick Bernhard’s excellent Borrowing from Mussolini: Nazi Germany’s Colonial Aspirations in the Shadow of Italian Expansionism:

[Reich] publications also justified acts of extreme violence committed by the [Fascist] military in its colonies. Although an estimated 100,000 people died in Libya because of [the Fascists’] murderous anti‐guerrilla policy against Arabs, Berbers and Jews,^75^ it was first and foremost the war in Abyssinia that received huge attention and media coverage in [the Third Reich]. As we now know, between 350,000 and 760,000 Abyssinians from a population of 10 million died during [Fascism’s] war of aggression and the subsequent occupation.^76^

During the conflict, which began in October 1935, [Fascist] armed forces under the command of Emilio De Bono and Pietro Badoglio not only made ample use of modern tanks, artillery and aircraft against a poorly equipped Ethiopian army, they also crushed military resistance with naked terror: they bombed undefended villages and towns, killed hostages, mutilated enemy corpses, established several forced labour camps, committed numerous massacres as reprisals, deported the indigenous intelligentsia and used poison gas not only against combatants, but also against cattle. By the end of the Ethiopian campaign in May 1936, the Royal Italian Airforce had deployed more than 300 tons of arsenic, phosgene and mustard gas.

For a documentary partly on the Fascists’ crimes in Ethiopia (partially NSFL), see Fascist Legacy.

In Somalia, the pattern was similar: widespread use of forced labor, use of the concentration camp, violence against dissidents, thousands dead, and forced marriages, among other worries.

Geoff Simons’s Libya: The Struggle for Survival, pages 122–3, 129:

[A Fascist]/Egyptian agreement in 1925 gave [the Fascist bourgeoisie] sovereignty over the Sanussi strongholds at the Jarabub and Kufra oases, making it easier for the [Fascists] to cut off the Libyans’ sources of supply in Egypt, but the conflict continued. The [Fascist] supply lines, communication facilities and troop convoys came under frequent attack, with the [Fascists] responding by blocking water wells with stones and concrete; slaughtering the herds of camels, sheep and goats that the tribes depended on; moving whole communities into desolate concentration camps in the desert; and dropping captured Libyans alive from aircraft.

[…]

There is a lengthy catalogue of war crimes perpetrated by General Graziani, for which he was never called to account. It is suggested that the [Fascists] deliberately bombed civilians, killing vast numbers of women, children and old people; that they raped and disembowelled women, threw prisoners alive from aeroplanes, and ran over others with tanks. Suspects were hanged or shot in the back, tribal villages — according to Holmboe — were being bombed with mustard gas by the spring of 1930. As with all atrocity tales, there is probably an element of exaggeration, but Holmboe noted that during the time he was in Cyrenaica ‘thirty executions took place daily […] The land swam in blood!’^41^

Few Libyan families survived this period without loss: Muammar Gaddafi himself lost a grandfather, and three hundred members of his tribe were forced by the [Fascists] to seek refuge in Chad. Graziani was well aware that the alleged atrocities, under his command, were tarnishing his military reputation: he noted the ‘clamour of unpopularity and slander and disparagement which was spread everywhere against me’, but recorded in his book, The Agony of the Rebellion, that his conscience was ‘tranquil and undaunted to see Cyrenaica saved, by pure Fascism, from that invading Levantism which sought to escape from the civilising Latin force’.

For an excellent reenactment of some of these events, see The Lion of the Desert (which historian Angelo Del Boca praised, saying that ‘it respects the historical truth’, but no reenactment is perfect, of course).

As the Allies sought to reclaim Libya, a new wave of white supremacist violence erupted, including (maybe surprisingly) against Jews. From Patrick Bernhard’s Behind the Battle Lines: Italian Atrocities and the Persecution of Arabs, Berbers, and Jews in North Africa during World War II:

Anti‐Jewish pogroms broke out in major Libyan towns such as Benghazi and Tripoli: [Fascists] plundered Jewish shops and beat or chased Jews in the streets.^34^ The governor‐general of Libya himself spoke of “excesses” committed by his compatriots in Benghazi, the capital of Cyrenaica.^35^ Roberto Arbib, one of the leaders of the Jewish community in Tripoli, wrote with regard to the violent assaults he witnessed in Libya’s capital: “[the Fascists] could not stand the sight of a single Jew.”^36^

Such attacks were almost unique in the history of Italian Fascism: in Italy itself, anti‐Jewish pogroms occurred only rarely. Similar persecution had taken place only in Trieste, in the contested borderland with Slovenia, where local Fascist leaders were fervently antisemitic.^37^

As for Eritrea, there were not as many obvious atrocities; the Fascists usually oppressed them in subtler ways. One maybe not so subtle way, though, was concubinage. Quoting Giulia Barrera’s Dangerous Liaisons: Colonial Concubinage in Eritrea, 1890–1941:

Generally speaking, Italian men categorized their Eritrean sexual partners as either “sciarmutte” or “madame.”^3^ Sciarmutta was an Italianization of the Arabic term “sharmãta” and stood for prostitute; the term madama applied to concubines who associated with Italian men, although Italian men and their madame did not always cohabit.

Fascism in the Balkans

Pictured: Fascist firing squad about to execute several Slovenian hostages.

The Fascist assault on the Greek isle of Corfu in 1923, which resulted in at least fifteen deaths, was but a brief taste of what the Fascist bourgeoisie had in store for the Balkans in 1939 and later. Albania, already exposed to Fascist neoimperialism in the 1920s and 1930s, soon succumbed to a Fascist invasion in the April of 1939. The invaders killed at least 160 Albanians, but the actual number might have been as high as 700. Either way, the worst was yet to come. To get an idea of the situation, here is a quotation from Bernd J. Fischer’s Albania at War, 1939–1945, page 114:

In August [1942] Tomori reported further decrees, including “All prefects in Albania are authorized to fix by order the delay during which all rebels in the district of a certain prefecture must give themselves up under penalty of death for infringers. The families of those who do not surrender will be interned in concentration camps, their houses burned and their possessions confiscated. These measures will also be taken for military deserters and for recruits who will not respond to the calling‐up orders.”^94^

It is difficult to say how many casualties in total the Italian Fascists inflicted, but Axis occupation overall caused nearly two and a half dozen thousand deaths. Pages 267–8:

Casualty figures vary rather widely. One of the first postwar Albanian newspapers, Luftari, estimated Albanian dead at 17,000.^23^ This figure was later revised upward by official Albanian government estimates and the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) to between 28,000 and 30,000, mostly from the south, out of a total population of about 1,125,000, or about 2.58 percent of the population. Some 13,000 were left as invalids.^24^

Now it was Greece’s turn (because apparently the Dodecanese islands from the 1910s weren’t enough to appease the Fascist bourgeoisie). After Fascist Italy’s unsuccessful invasion of Greece in late 1940, the Third Reich seized Greece in April 1941 and transferred it to Fascist Italy. Here are some examples:

They introduced a new tax system, while the judges applied the mandatory [Fascist] law and tried in the name of the Italian king. They opened camps for “disobedient Greeks” in Paxos, Othoni and Lazaretto, where approximately 3,500 Greeks were jailed, tortured and executed under harsh conditions.

[…]

The most characteristic case was the massacre in the village of Domenico, where on February 13, 1943 [Fascist] soldiers burned the village and murdered 194 people, including women and children. Approximately in the same area one month later, on March 12th, 1943, the [Fascists] burned Tsaritsani to the ground and executed 40 villagers. On June 6, 1943, in retaliation for the bombing of a rail tunnel by the resistance in the vicinity of Kournovo (central Greece), the [Fascists] executed 106 Greeks.

Half of Yugoslavia was next. (Possibly NSFL.) Quoting Capogreco’s Mussolini’s Camps: Civilian Internment in Fascist Italy (1940–1943), page 1:

In the Yugoslav territories occupied or annexed after the [Axis] invasion of April 6, 1941, [Fascist] forces often resorted to repressive methods that included the burning of villages, shooting of civilian hostages, and deportation of local people to special concentration camps “for Slavs.”^2^

Set up in [Fascist] Italy and in the occupied territories, and almost always supervised by the Italian Armed Forces, these camps forced internees to endure a restrictive and harsh internment that led to thousands of deaths, including those of many children.

Page 54:

In Yugoslavia, the Italian Army used civilian internment as part of its violent and deliberately racist occupation that included the burning of villages and the execution by firing squad of civilian hostages, behaviors that created in local populations “a trail of resentment against the Italian community that, still today, hardly abates.”^46^

For a documentary partly on the Fascists’ crimes in Yugoslavia, see Fascist Legacy.

Some Greeks and Yugoslavs would also, quite literally, share their suffering. Page 29:

Typically, in the reports written by Red Cross representatives, there emerged significant differences in the treatment given to British and French prisoners, and that reserved for Yugoslav and Greek ones. The latter, typically housed in precarious and decrepit structures, often lamented the violations of the articles 36–41 of the Geneva Convention.^149^ Even when they were in the same camps with British and American soldiers, their conditions often remained pathetic.

Fascism on the Eastern Front

Pictured: Several Soviets that the Fascists killed.

Even Soviet documents acknowledge that the Italian Fascists on the Eastern Front were quite restrained in comparison with their allies; most of them were gentler with the civilians than the other Axis forces. Quoting Bastian Matteo Scianna’s The Italian War on the Eastern Front, 1941–1943: Operations, Myths and Memories, page 248:

Soviet postwar accusations were themselves moderate: only 36 Italians were charged with war crimes,^135^ and the files show a notable difference between the German and Hungarian actions on the one hand, and the Italians’ on the other: only five per cent of 175 asserted war crimes in the Voronezh area were associated with Italian (Alpini) troops.^136^

Yet, as that very fragment implies, there were certainly exceptions. Pages 246–7:

The Italians, still, were generally “not regarded as terrible looters during the war,”^124^ or as prone to rape (as much evidence about the Romanians and Hungarians indicates).^125^ Nevertheless, the Germans reported “rather unpleasant instances in regards to behaviour towards the civilian population” by the XXXV Corps (former CSIR) when it moved eastwards after a long winter rest,^126^ and the Italians were involved in oppressive measures such as the burning of villages, shooting innocents, forced prostitution and pillaging.^127^

But, exceptions or not, the otherwise neighbourly Fascists were still accomplices in a massive colonial war of extermination, and that alone should call their character into question. Page 238:

Undoubtedly, the [Regio Esercito] were no saints and did take part in a war of aggression that resulted in the death of millions of soldiers and innocent civilians.

In sum, Patrick Bernhard’s Renarrating Italian Fascism: New Directions in the Historiography of a European Dictatorship indicates that overall,

One simply cannot forget that over one million people died as a consequence of this vision — mostly in Africa, but also in the Balkans — in the wars of conquest and occupation waged by the Italian Fascist régime.

(Emphasis added in all cases.)

Kubijovyč was an infamous Nazi collaborator, a founder of the 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS as head of the [Axis’s] Ukrainian Central Committee. In a 2012 paper in the Journal of Slavic Military Studies, Rudling, now a historian at Lund University in Sweden, describes Kubijovyč as “an enthusiastic proponent of ethnic cleansing” who wanted to establish an independent Ukraine without Jews or Poles.

“The formation of the Galician-Ukrainian division within the framework of the SS, is for us not only a distinction, but our responsibility that we will continue to [support] and maintain this active decision, in cooperation with the German state organizations, until the victorious end of the war,” Kubijovyč said on April 28, 1943, the day the division was formally established.

“This historic day was made possible by the conditions to create a worthy opportunity for the Ukrainians of Galicia, to fight arm in arm with the heroic German soldiers of the Army and the Waffen-SS against Bolshevism, your and our deadly enemy. We thank you from our heart. Of course we ought to thank the Great Führer of the united Europe for recognizing our participation in the war, that he approved your initiative and agreed to the creation of the Galicia division.”

After the war, Kubijovyč edited the first two volumes of the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, which downplayed the Galicia Division’s [Axis] ties. His family’s endowment was specifically for the purpose of completing the encyclopedia’s translation into English.

When Rudling and fellow historian Tyrik Cyril Amar questioned the propriety of Kubijovyč’s endowment in a 2015 article for History News Network, CIUS director Volodymyr Kravchenko accused them of “assaulting the dead” and “mudslinging … to conduct an information war in which the opponent is not convinced but destroyed.”

Kubijovyč was also pictured with Peter Savaryn on the cover of the 1976 book, The Politics of Multiculturalism by Manoly Lupul. The photo is of the signing of a contract between the CIUS and the Shevchenko Scientific Society of Europe to collaborate on the Encyclopedia of Ukraine.

Left image: Peter Savaryn (left standing) and Volodymyr Kubijovyč (center sitting) pictured here at the 1976 contract signing between the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies and Shevchenko Scientific Society of Europe to collaborate on the Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Right image: Volodymyr Kubijovyč (circled in red) gives a [Fascist] salute at the 14th Waffen-SS recruitment ceremony in 1943.

Events that happened today (October 10):

1895: Wolfram Karl Ludwig Moritz Hermann Freiherr von Richthofen, Axis field marshal, was born.

1935: A parafascist coup d’état terminated Greece’s Second Hellenic Republic and replaced it with the Kingdom of Greece (again).

1938: Abiding by the Munich Agreement, Czechoslovakia completed its withdrawal from the Sudetenland, now property of the Third Reich.

1942: Arnold Majewski, Axis cavalry officer, died immediately after receiving a bullet from a Soviet sniper.

1957: Karl August Genzken, Axis physician who committed numerous atrocities against concentration camp prisoners, was kind enough to drop dead.

In Fascist Italy, “Columbus Day” was created by Mariano Lucca, a failed politician turned reporter who interviewed Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini. It was likely intended to dismiss and normalize the well known atrocities that Columbus committed. Its introduction to Imperial America, however, was more complex:

To truly understand Columbus Day, one must learn about an important name in Italian‐American history: Generoso Pope.

In 1937, following the popularity and success of newspaper magnate Generoso Pope’s New York City Columbus Day Parade, President Franklin Roosevelt declared October 12th a national holiday commemorating Christopher Columbus’s “discovery of North America.” Although the Italian‐born, Brasilia‐affiliated explorer sailing under the Spanish Empire failed to ever set foot on the North American continent, Italians in America had accrued a kinship to the famed navigator.

[During the 1920s and ’30s, the Fascist Party in Italy courted Italian immigrant communities in the U.S., which they considered “colonies” of the [Fascist] state. The Fascists and their sympathizers helped organize the first U.S. Fascist convention in Philadelphia and lobbied to make Columbus day a national holiday. (Source.)]

While Pope’s Columbus Day Parade (starting in 1929) was not the first celebration of Columbus that New York had seen, his would quickly become a tradition there. While the establishment of a formal Columbus Day may seem to be an outwardly straightforward process, a deeper dive into Pope’s involvement with powerful political players reveals a profound meaning of the holiday that extends beyond the mere celebration of Columbus himself.

During the Depression Era, Pope was considered one of the most impactful political power brokers within the Democratic Party, and he would eventually be appointed the head of the Italian division within the Democratic National Committee by President Roosevelt himself. Pope owned seven Italian‐language newspapers as well as the radio station WHOM, and his flagship paper, Il Progresso Italo‐Americano, was the largest Italian‐language newspaper in the United States with a circulation nearing 200,000 copies (he had, notably, purchased the paper from a lesser‐known owner for the modern‐day equivalent of $261 million).

The source of Pope’s political power resided in his influence over the Italian‐American voting bloc through his newspaper empire, as Italian immigrants depended on his papers for a sense of community and for news written in their native language. Galvanizing the Italian voting bloc, Pope played a pivotal role in securing elections for various New York City politicians and judges.

But Pope also played a significant role in world affairs: He was considered one of the most influential fascist propagandists in the U.S. for Mussolini’s […] régime. To provide a few significant examples of his fascist status, Pope was a member of the fascist Lictor Federation and its predecessor, the Fascist League of North America (FLNA); he employed multiple known fascists; he was photographed performing a fascist salute in Rome in 1937; lastly, he was awarded the honorary title of Grand Officer of the Crown of Italy for his service to fascism in America.

Following the FLNA’s disbandment in 1929, the type of propaganda that was perpetuated within the U.S. began to shift from the domain of politics to that of culture, bolstering Italian nationalistic sentiments in immigrants and second‐generation Italian‐Americans to create, as one history of early 20th century Italian immigrants put it, a people “spiritually tied to fascist Italy by linguistic [and cultural] bonds.”

Following his first successful Columbus Day parade, Pope met in March 1930 with FDR, then governor of New York, to discuss the potential for a state holiday in celebration of Columbus. Although the idea was received favorably, Pope lacked the necessary political capital to get it enacted.

Four years later, following Roosevelt’s 1932 presidential victory, the fascist newspaper kingpin petitioned the president to reconsider his previous stance on the Columbus Day holiday. In a nod to Pope’s prolonged help to FDR through consistently favorable coverage in his papers, as well as to acknowledge recent race‐based hate crimes committed against Italian immigrants and a sign of appreciation for their turnout in the recent election, President Roosevelt declared October 12th a national holiday. With the establishment of Columbus Day, Generoso Pope had succeeded in solidifying Christopher Columbus’s place in U.S. history and within the minds of Italian‐Americans as a near‐mythic entity.

Columbus Day and Pope’s Columbus Day Parade were both founded with fascist ideologies in mind, which was clear and ever‐present at the New York City parades prior to World War II. At the 1936 parade, according to one account, prominent politicians were implored by anti‐fascists not to attend, as “local fascist papers have announced that uniformed Fascisti will participate in military formation.”

In 1937, when FDR declared Columbus Day a federal holiday, spectators at the subsequent parade allegedly cheered loudly and raised their hands in the infamous fascist salute when Italy’s fascist anthem, “Giovinezza,” was played. The next year’s parade, the New York Times reported, saw spectators shouting “Viva Mussolini” along the route.

When Mussolini’s Italy declared war on the U.S. on December 11, 1941, hundreds of known fascist sympathizers were quickly incarcerated by the government for their enemy activities. Fortunately for Pope, in the weeks prior to the war’s declaration, he had begun distancing himself from Mussolini’s fascism and even publicly declared “fealty to the U.S.” in an October 1940 New York Times article.

Though many of these incarcerated fascists were his known associates, Pope continued advising FDR and the Democratic National Committee regarding Italian‐Americans, particularly during the 1944 election. [Among other things, Generoso Pope also ordered mobster Carmine Galante to murder the antifascist journalist Carlo Tresca in 1943. Pope’s son, Generoso Jr., was a CIA officer who founded the National Enquirer with loans from Frank Costello and Roy Cohn, and ran the paper like an intelligence‐gathering network where two subjects were off limits: the CIA and the mob.]

(Emphasis added.)

In 1925, Benito Mussolini declared Columbus Day a national holiday in Fascist Italy:

[Transcript]

“COLUMBUS DAY.”

Italy’s New Holiday.

For the first time in Rome and throughout Italy on October 12, by order of Signor Mussolini and the National Government, “Columbus Day” was celebrated as national holiday. It is strange, but true, that it took more than 400 years for Christopher Columbus to obtain the generous recognition due to him from his own countrymen, and for the date of the discovery of America to be commemorated with national honors in Italy an well as in America. The re‐evaluation of one of the greatest national glories of Italy is due to the enlightened policy of the Fascist Government, which some months ago issued a proclamation, signed by Signor Mussolini, that hereafter October 12, the date of the discovery oi America by the Genoese navigator, was to be celebrated as a national holiday.

The national flag was hoisted on all public buildings, and on some private houses. The general public has not yet learned the significance of the event. In Rome a commemorative ceremony was held

[sic]

(Source.)

Furthermore, Fascist Italy used a 1927 monument dedication in Richmond to spread propaganda and declared fake news about atrocities it was actively committing:

[Transcript]

ROME’S AMBASSADOR SAYS ITALY FOR PEACE

Mussolini’s Government Placed in Wrong Light by False Propaganda.

“Fake propaganda” [sic!] from abroad was ascribed by Nobile Giacomo de Martino, ambassador to the United States from Italy, at the Columbus monument dedication exercises here yesterday, as tending to show up the Italian government in a false light as regarding its peaceful attitude toward other nations. Such propaganda, he declared, would make it appear that Italy was at war with “all the world at the same time.”

(Source. Footnote. On a related note, I read that a ‘Mussolini groupie’ donated the statue in San Francisco near Coit Tower.)

Italian‐Americans in RI commemorated the [WWI] Battle of the Piave River, the March on Rome, the Birth of [Ancient] Rome, and Columbus Day with fascist salutes, with a (controversial) 1937 Columbus Day parade in West Warwick even featuring Black Shirts marching in formation.

[Transcripts]

RELIEF BAN VOTED ON BLACK SHIRTS

West Warick Committee Acts to Purge Rolls as Policy in the Future.

RESULT OF RECENT PARADE

Agitation Began After Marchers on Columbus Day Gave Fascist Salute; Veterans Resentful

BLACKSHIRTS FACING BAN

West Warwick Council Votes to Withhold Parade Permits

The presence of blackshirts in the Columbus Day parade in Natick earlier this month last night drew the attention of the West Warwick Town Council, which approved a triple resolution aimed at discouraging the practice in the future.

(Source.)

Events that happened today (October 9):

1907: Horst Wessel, SA officer and musician, was unfortunately born.

1908: Werner von Haeften, Axis lieutenant who failed to oust the Third Reich’s Chancellor, was delivered to the world.

1934: An Ustashe murdered King Alexander I of Yugoslavia and Louis Barthou, Foreign Minister of France, in Marseille.

1937: Somebody massacred nine Catholic priests in Zhengding, China who were protecting the local population from the advancing Imperial army.

1941: The Kingdom of Romania deported Jews to Transnistria. (Hence this day is known as the National Day of Commemorating the Holocaust in Romania.)

1945: Gottlieb Hering, SS commander involved in Action T4, took his long overdue dirtnap.

1947: Yukio Sakurauchi, Imperial Minister of Commerce and Industry, expired.

1959: Shirō Ishii, the Axis director of Unit 731 and later contributor to the U.S. biological warfare program, did a nice thing for once and dropped dead.

1974: Oskar Schindler, a moderate fascist who famously saved (but occasionally abused) hundreds of Jewish workers, perished.

1976: Walter Warlimont, Axis staff officer, died.

1988: Felix Wankel, Axis engineer and SS member, departed from the world.

Similarly to how there were both good Christians and extremely sinful Christians in relation to the Shoah, there were both good Muslims and deeply sinful Muslims with regard to it as well. It was common (maybe less so now) for Islamophobes to emphasize the anti‐Jewish Muslims, for example the 13th Waffen Mountain Division of the SS Handschar, but given the rise of the alt‐right it would be unsurprising if some Islamophobes would now prefer to emphasize the Jew‐friendly Muslims such as the Albanians.

In any case, while some ultranationalist Muslims did mistake the European Fascists for allies against colonialism, most Muslims didn’t want the snake oil that the Axis was offering. Many of them had the circumspection to tell that the Fascist colonialists were no better than their liberal counterparts, and Libya was a case in point.

What too many of us overlook is that the Western Allies weren’t the only ones holding colonies in North Africa. So was the Axis, giving many Muslims and Jews alike a common enemy:

France, an important colonial force in North Africa and Nazi Germany in Libya and later in Tunisia, enforced many anti‐Semitic laws against the Jews in 1940, including the Statut des Juifs, which was approved by Algeria and Tunisia, and in Morocco the Sultan Muhammad V approved the Moroccan version of Statut des Juifs. These laws forced Jews into labor, punishment, and isolation camps.

In 1942 at the Wannsee conference (Satlo, 2006: 26–27) plans for the final solution of the Jewish question exacerbated the situation for Jews all over the world, including northern Africa. The […] Fascist […] colonial takeover of Arab countries for strategic reasons also included the goal of exterminating Jews from these countries. Muslims, although generally unaware of the death camps in Europe, had the direct knowledge of Jews being interned in their own countries, but the Jews were perceived as the allies of the colonial forces and not necessarily Arabs.

[…]

However, the story of colonization reemerges when the discussion of Arab camps surface in Muslim and Jewish narratives, and the two minor narratives emerge within their own minority status in witnessing both the colonial forces and the [Fascist] campaign. In other words, Jewish and Muslim identity struggled immensely through the time of the Holocaust from the fall of the Ottomans 1922, colonialism, and the oppression and Holocaust of native Arab/Muslim/Jewish narratives.

The historical accounts of Jews from Europe or Arab lands who tried to escape ended up in many death camps, and the Arabs who fought against the colonists and attempted to overthrow the colonial forces landed in camps in the Sahara and in some cases with Jews. For example, many Jews who had fled Germany in 1938–1939 were later captured in France and interned in Arab camps.

The camp at Hadjerat‐M’Guil was opened on November 1, 1941, as a punishment and isolation camp. It contained 170 prisoners, nine of whom were tortured and murdered in conditions of the worst brutality. Two of those murdered were Jews, one of whom had earlier been in a concentration camp in Germany but had been released in 1939 and had fled to France. This young man’s parents had become refugees in London. On learning of their son’s murder in the Sahara, they committed suicide (Glibert, 1988: 56).

[…]

Berkani’s testimony says that he and the Jews in the camp understood that Deriko was trying to get the Arabs to fight with Jews:

He gathered the Jews of the camp, who were previously mixed with the Europeans, and separated them from the French, or rather from the Europeans. This cursed Dériko prepared further provocations once again. Europeans were separate, the Arabs were separate, and the Jews too were separate. Now the Jews were also gathered in the first section. (Berkani, 1965: 44)

Berkani, a Muslim, sees Deriko’s tactic and writes the following; he observes astutely that the [Fascists] (Vichy) were attempting to create tension but that the Jews and Muslims (he changes from Arabs) had caught onto his divisive tactic.

There is no doubt that Dériko did this with the intention of seeing the Jews cut down and killed by the Muslims, since the Jews were not numerous. But the Jews realized his goal; the Arabs too realized the same thing. Commander Dériko expected that there would be fights between Arabs and Jews, but the opposite occurred: a friendly understanding spread between the two communities. Never could one have believed that the Arabs and the Jews in the first section of the camp would become real friends, even brothers. Whether you wish to believe it or not, they were moreover brothers in hunger, in suffering, in misery, in punishment/pain etc. […] in Dériko’s camp. (Berkani, 1965: 45)

(Emphasis added.)

Related: Remembering the Muslims Murdered at Auschwitz

Events that happened today (October 8):

1884: Walter Karl Ernst August von Reichenau, Axis Field Marshal who was partly responsible for the Babi Yar massacre, polluted the earth.

1888: Ernst Kretschmer, Axis psychiatrist, was born.

1910: Helmut Kallmeyer, Axis chemist who was involved in Action T4, forced his existence on us.

1939: The Third Reich annexed western Poland.

1941: During the preliminaries of the Battle of Rostov, Axis forces reached the Sea of Azov with the capture of Mariupol.

1943: Friedrich Schubert's paramilitary group executed approximately thirty civilians in Kallikratis, Crete.

In November 2022, the Ukrainian Youth Association, also known as “Soom,” (SUM—Spilka ukrayinsʹkoyi molod—or CYM—Спілка української молод) held its 20th World Congress in Hanover Township, New Jersey. Supposedly an “isolationist” attitude dominated: CYM, despite its plummeting membership, “should be for privileged people only.”

Well, they’re certainly right when they say that it’s for privileged people only, but not necessarily in the way that they had in mind. (I think that the photograph speaks for itself.)

Just over 50 delegates participated in the World Congress on behalf of CYM branches in Ukraine, Estonia, Germany, Belgium, Spain, Portugal, Britain, Australia, Canada, and the United States. After years of singing, “now a SUMivtsya,” (member of CYM) “tomorrow a fighter,” CYM adopted a new slogan for the upcoming year: “now a fighter.” In 2023 the organization vowed to commemorate the 140th birthday of Dmytro Dontsov (1883–1973), a fascist ideologue who translated Mein Kampf.

[…]

Longtime readers of the Bandera Lobby Blog may remember that George Borec, a veteran of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, the 1940s military wing of OUN-B, got a street in Penrith, Australia named after Stepan Bandera, and financed the construction of a nearby Banderite youth center in a suburb of Sydney. The local branch of CYM has since relocated to a newer building, where visitors are greeted at the front entrance by portraits of far-right OUN leaders (Bandera, Konovalets, Shukhevych, Stetsko) and Symon Petliura, a World War I-era figure whose military forces carried out pogroms against Jews.

I froze upon reading this.

According to historian Per Rudling, the “Roman Shukheyvch Ukrainian Youth Unity Complex” affiliated with CYM in Edmonton, Alberta was opened in 1973 with significant funding from the provincial government. In 2020, he explained, “The purpose of the complex, the OUN(b) press declared, was to ‘become a blacksmith’s forge, which will forge hard, unbreakable characters of the Ukrainian youth’ and to ‘raise and harden a new generation of fighters for the liberation of Ukraine…’”

Meanwhile, I reported that the federal government awarded the Banderites $279,138 to “repair” the complex in 2015, and CYM-Canada charged to the defense of the Ukrainian Waffen-SS monument in Oakville after it became the subject of an international news story.

They’ve been much more quiet about the recent “Nazigate” scandal…

CYM-Canada published this imagine in 2020 after the Ukrainian Waffen-SS monument in Oakville was vandalized with anti-Nazi graffiti.

‘KNOW THE FACTS, NOT THE ~~PROPAGANDA~~’. Finally we can agree with these anticommunists on something.

In 1991, SNUM was reformed as the official branch of CYM in Ukraine. From 2005 through 2016, it received over $400,000 in grants from the U.S. State Department via the National Endowment for Democracy. From 2016 until 2019, CYM and another, more radical OUN-B youth group in Ukraine were members of the Reanimation Package of Reforms Coalition, the “largest and most visible reform network” in the country, which has been funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development and Global Affairs Canada.

The NED…we meet again.

Events that happened today (October 7):

1866: Włodzimierz Halka Ledóchowski, Fascist sympathizer, was born.

1900: Heinrich Himmler, Axis commander and politician, stained the human race for all time.

1904: Armando Castellazzi, one of Fascist Italy’s professional footballers and managers, started his life.

1920: Georg Leber, Luftwaffe member, was delivered to the world.

1923: Irmgard Ilse Ida Grese, SS officer and concentration camp guard at Ravensbrück and Auschwitz… I don’t even want to say it. Just thinking about her makes me mad.

1940: Arthur H. McCollum proposed bringing Imperial America into the war in Eurasia by provoking the Empire of Japan into assaulting one of the U.S. colonies.

1944: During an uprising at Birkenau concentration camp, Jewish prisoners burnt down Crematorium IV (as portrayed in the excellent motion picture, The Grey Zone). Meanwhile, Helmut Lent, Axis night‐fighter ace, died having suffered injuries in a crash landing two days earlier.

2014: Siegfried Lenz, Fascist and Kriegsmarine draftee, expired.

(Mirror.)

The statement from the Governor General — the representative of the British Monarchy in Canada — concerned Peter Savaryn, who served as chancellor of the University of Alberta from 1982 to 1986 and in 1987 was appointed to the Order of Canada. The award is akin to the U.S. Presidential Medal of Freedom, and is considered the second highest distinction for Canadians, topped only by the Order of Merit available to all citizens of the British Commonwealth.

Responding to an inquiry from the Forward, the statement from Governor General Mary Simon expressed “deep regret” about Savaryn’s appointment. A spokesperson said the office is also now reviewing two other honors it gave Savaryn: the Golden Jubilee (awarded in 2002) and Diamond Jubilee (awarded in 2012) medals.

[…]

Hunka and Savaryn were both volunteers in the 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS, commonly known as SS Galichina or the Galicia Division. The unit, which was formed in 1943 out of recruits from the Galicia region in western Ukraine, was armed and trained by the Third Reich, and commanded by German SS officers. It’s accused of war crimes, including burning alive 500 to 1,000 Poles in 1944.

Related: Trudeau says Canada may finally make secret Nazi files public

Events that happened today (October 6):

1900: Willy Merkl, a mountain climber whom the Third Reich briefly sponsored, was born.

1916: Chiang Wei‐kuo, Japanese–Chinese Wehrmacht(!) officer candidate, was brought to the world.

1935: Fascist forces captured Adwa.

1939: The Battle of Kock became the final combat of the September Campaign in Poland.

1942: American troops forced the Axis from its positions east of the Matanikau River during the Battle of Guadalcanal.

1943: A paramilitary group in Crete burnt thirteen civilians alive during the Axis occupation of Greece.

1944: Units of the 1st Czechoslovak Army Corps entered Czechoslovakia during the Battle of the Dukla Pass. (This later became Deň obetí Dukly or Dukla Pass Victims Day in Slovakia.)

1945: Leonardo Conti, SS‐Obergruppenführer who was involved in the massacre of hundreds of thousands of disabled people, hung himself in prison… no comment.

In attempting to achieve a united front among Germany, Poland and Japan against the USSR, the [Imperial] Japanese were frequently reminded by the Poles that they had reached their agreement with the USSR not out of any genuine friendship but rather of the need to protect their rear against a Germany that was growing stronger every day. The head of Polish military intelligence, for example, stated on 12 December 1933:

Germany has rearmed itself at the present moment to a far greater extent than anyone assumes. The Polish General Staff is better informed in this respect than France for example.^54^

Despite the complaints in the [Imperial] press about Polish betrayal of the old relationship against the USSR, the Polish government demonstrated its difficulties eloquently by reaching a parallel non‐aggression pact with [the Third Reich] in January 1934. When asked about the reasons that lay behind the Nazi view of this episode by Mussolini in Venice in June, Hitler replied:

Ten years ago, Poland had been militarily stronger than Russia. But now she no longer was. She had concluded the pact with us out of fear of Russia.^55^

For the [Imperial] Army, the year 1934 was regarded by many as a target date for [Imperial] Japan to be in a position to catch up with the Soviet union and challenge it. Decisions were taken in 1932 to strengthen the attaché bureaux in Paris, Berlin and Warsaw and this was followed in the spring of 1934 by the appointment of outstanding officers to the attaché posts, Major‐Generals Ōshima Hiroshi in Berlin and Yamawaki Masatake in Warsaw.^56^

Both officers pressed their hosts to support a deepening of bilateral relations with the [Imperial] Army. The press pointed to the ‘rumour of Japanese–Polish collaboration’ in the course of 1934 and to claims about the existence of ‘the closest collaboration between the Japanese and Polish intelligence services — at least so far as Russia is concerned’.

The [Third Reich’s] military attaché in Warsaw, Major‐General Schindler, noted that ‘the bureau of the Japanese military attaché here operates as a sub‐office of the Japanese Intelligence Division by assembling all information gathered in Europe about foreign armies, and especially about Russia’ and that Yamawaki was the driving force behind this. ‘If the information reaching me is correct,’ he continued, ‘not only Lieutenant‐Colonel Fujizuka, but also General Yamawaki himself has an office in the Intelligence Section of the Polish General Staff’.^57^

He then went on to report that Le Temps carried fresh allegations about the signing of an agreement in December 1934 for collaboration between the two general staffs that included arrangements to collaborate over military training, aviation and infantry equipment. It was also claimed that in the event of war, they would exchange raw materials and military equipment and that Poland would look after Japanese interests at the League, from which Japan was due to depart finally on 27 March 1935.^58^

Schindler accepted that it was quite evident that there was an existing arrangement over training in the sense that exchanges and secondments were already an established fact. However, he did not believe that any agreement extended beyond benevolent neutrality to mutual exchange of goods and equipment in wartime.^59^

The former Polish ambassador to Tōkyō and minister of foreign affairs, Tadeusz Romer, always denied the existence of any treaty with Japan, though it would not follow that the General Staff would necessarily think itself bound to disclose any technical military arrangements, particularly if these were not committed to paper and signed by both parties.^60^

[…]

This suggests, therefore, that there had at least been some kind of oral agreement between the Polish and Japanese General Staffs about the Soviet Union, but it is quite likely that it was not consigned to paper, or at least not signed and that it was something limited to the knowledge of the military — a situation permissible in the [Imperial] system, if not the Polish.

It is also very clear that there was informal co‐operation between Polish and [Imperial] military attachés in different capitals outside Warsaw and Tōkyō. Polish military relations with the general staffs and staff officers from Sweden, Finland, the Baltic States and Rumania permitted [Imperial] Army officers to obtain information indirectly and directly from them all in the inter‐war period, as can be seen in the co‐operation in Riga in the 1930s between Colonel Onodera and Major Brzeskwinski.^69^

Though collaboration extended to exchange of information on Soviet codes and cyphers, there is absolutely no evidence that anything was said to the [Imperialists] about the Polish successes in reading the cypher messages sent by means of Enigma machines by the [Wehrmacht].

While efforts to draw Poland into the anti‐Comintern arrangement succeeded in so far as police co-operation about Communists was concerned, all efforts to try to persuade the Poles to move into a more active role proved in vain, in spite of the efforts of [Imperial] personnel in Europe. Warsaw continued to function as a centre for intelligence‐gathering about the USSR until 1939, when the Polish leadership firmly rejected [Berlin’s] efforts to reincorporate Danzig in Germany by negotiation and accepted Chamberlain’s guarantee.

The deal with the Soviet Union in August 1939 in the middle of the negotiations for an alliance among Japan, Germany and Italy sealed not only the fate of Poland and the Baltic States, but it also led to a highly disagreeable outcome to Soviet–Japanese confrontation over Outer Mongolia and a denunciation of Hitler for abandoning the secret agreement attached to the Anti‐Comintern Pact.

#Regrouping after the Destruction of Poland

The failure of [Imperial] mediation efforts and the elimination of the Polish state, coupled with the resentment at [Berlin’s] expedient arrangements with the Soviet Union, made it possible for Polish military officers who escaped via Rumania and Lithuania to France and Britain to continue to support the old arrangements with Japan, even after Japan joined the Tripartite Pact in September 1940.The [Imperial] Army was forced to transfer its intelligence work directed toward the USSR from Warsaw to Riga, Helsinki and Stockholm, but succeeded in maintaining contact with Polish officers working underground after the Polish defeat, though many others were able to make contact with British, French and Soviet recruiters in countries like Rumania.

(Emphasis added.)

1912: Fritz Ernst Fischer, Axis doctor who performed medical atrocities on inmates of the Ravensbrück concentration camp, polluted humanity.

1921: Adolf Schicklgruber gave a speech in which he explained the NSDAP’s flag’s significance.

1938: The Third Reich invalidated Jews’ passports.

1943: Axis forces on Wake Island executed ninety‐eight American POWs.

The context for this was that Oswald Mosley formed a party called the British Union of Fascists in 1932. By 1936 he was having a hard time, he wasn’t doing as well as he thought [that] he was going to do, so Mosley had hit a roadblock, he was making no progress. He decided that one way of breaking through electorally was to galvanize anti‐foreign sentiment, anti‐Jewish sentiment, anything against the other, and the place to do that was the East End of London, which had brought everybody together.

The East End of London was always the melting pot of British society, and he could specifically target the Jewish population of the East End of London. So he decided, after a campaign of about nine months in which he was using his thugs to intimidate people, to smash windows, to come down here and say, ‘We can do this, look, we are going to take on the foreigner in British society!’ What happened?

Mosley, dilettante that he was, turned up late—he apparently was on his way to a wedding in [the Third Reich], his own wedding, presided over by Joseph Goebbels, and he decided that things weren’t going to plan. Local Labour dignitaries decided that things were getting too fraught and negotiated with the head, the commissioner of the police. Somebody called Commissioner Games [sic], and they decided to point the fascists in the other direction. So instead of trying to get into the East End, they marched away along the embankment.

Other events that happened today (October 4):

1881: Walther Heinrich Alfred Hermann von Brauchitsch, Axis field marshal and the Wehrmacht’s Commander‐in‐Chief, decided that life wasn’t shitty enough for us, so he had to come along.

1892: Engelbert Dollfuß, Austrofascist Federal Chancellor, plagued the earth.

1903: Ernst Kaltenbrunner, lawyer, general, and the Reich Security Main Office’s director, arrived so that he could embarrass the human race.

1976: Francis Joseph Collin sent out letters to the park districts of the North Shore suburbs of Chicago, requesting permits for the NSPA to hold a white power demonstration.

1997: Otto Ernst Remer, a Wehrmacht officer who was partially responsible for German neofascism, dropped dead.

2009: Günther Rall, Wehrmacht major and Luftwaffe aviator, expired.

Quoting Carl T. Schmidt’s The Corporate State in Action: Italy under Fascism, pages 135–6:

Yet despite the efforts of the Fascist régime to salvage property interests and promote recovery, Italy was in an unhappy condition at the end of 1934. For, after more than ten years of power. Fascism had been unable to solve Italy’s economic difficulties.

Mussolini was forced to admit: ‘We touched bottom some time ago. We shall go no farther down. Perhaps it would be hard to sink any lower. . . . We are probably moving towards a period of humanity resting on a lower standard of living. We must not be alarmed at the prospect. Humanity is capable of asceticism such as we perhaps cannot conceive.’^23^

Not long after, in inaugurating the Corporations, he announced: ‘One must not expect miracles.’^24^ Industrial production remained at low ebb, foreign trade still fell off, unemployment was at a distressingly high level and efforts to combat it had had little substantial effect. All this was very harmful to Fascist prestige.

Continued economic troubles and the inner pressures of Fascism impelled the Dictatorship to seek escape in foreign fields. War might be a kind of public works vastly more effective in reviving industry than anything tried before. With their attention focused on the glories of the battlefield, the people might be diverted from an uncomfortable concern over their domestic misfortunes. And certainly a military victory would solidify the Fascist movement and restore its fading glamour.

In this crisis, the rulers themselves would learn that the machine they had built under whose dominion men must live in constant spiritual tension, in fear and uncertainty is above all an engine of warlike enterprise.

(Emphasis added.)

For many Africans, this was the real start of World War II, and Fascism’s reputation in the liberal régimes would never be the same. Ethiopia was the only nation‐state in Africa to have successfully resisted European imperialism up until this point, and the invasion was so shocking to the world that even many otherwise profascist Japanese were appalled (for a while).

It cost the lives of at least 350,000 Ethiopians, involved numerous unpunished war crimes, and brought Europe’s two Fascist empires closer together, serving as an important inspiration to the Third Reich. Its importance can hardly be overstated, but I suspect that many of us know little to nothing about his tragedy thanks to Eurocentrist education.

Now, concerning the documentary: it is a bit crude and archaic at times, and being made for television it inevitably suffers from time constraints, but it is still quite good for beginners and anybody who is more orientated towards visual learning. It also provides examples of U.S. attitudes towards Mussolini pre‐1935, something that antisocialists rarely discuss.

Alternatively, Lion of Judah is an hour longer and is lush with precious archived footage, but it almost feels like a stereotypical nature documentary with its painfully long pauses between narrations, its lengthy shots of almost everything that the Italians and Ethiopians were doing (from dancing to pedestrianism), and the subtitles are difficult to read, but beggars can’t be choosers. (There are a few modern, amateur documentaries available, but I’m reluctant to recommend them given that the authors are centrist chumps.)

Further reading:

*The Invasion of Ethiopia – Mussolini’s […] Plan For Restoration of the Roman Empire*

My humblest request is that we not let the memory of this tragedy fade away. Where other educators have failed in their duty, we must not fail in ours.

Other events that happened today (October 3):

1894: Walter Warlimont, Deputy Chief of the Operations Staff of the Third Reich’s Armed Forces High Command, blighted the earth.

1904: Ernst‐Günther Schenck, SS doctor, joined him.

1940: The Vichy government promulgated the Law on the status of Jews, which reduced France’s Jews to second‐class citizens.

1942: An Axis V‐2 rocket reached a record 85 km (46 nm) in altitude.

1943: Axis forces massacred 92 civilians in Lingiades, Greece.

Babi Yar is a giant, giant thing. It’s, you know… the Holocaust was essentially two parts: it was the death camps that’s represented by Auschwitz, and it’s the Holocaust by bullets which is just—it was just so often ignored, which is just taking Jews out in pits and shooting them, invariably with the help of local collaborators, and Babi Yar was when thirty‐three thousand Jews were killed in two days. In two days. Okay.

And, you know, there’s—Ukraine is filled with them. I mean, you know, my city Kharkiv has Drobytsky Yar, you know, fifteen‐thousand Jews in two days. It’s, it’s…it’s just, that’s how it is, and… but Babi Yar [is] the Auschwitz of the Holocaust by bullets. And it’s this giant, sprawling ravine—again, thirty‐three thousand bodies, you have to point [out], you know—um… and it has been the target of so much attempts at perversion from various sides.

In 2016, I believe, 2016 and 2017, um…during commemorations of Babi Yar, the Ukrainian government did this despicable thing, which is they put up a temporary display with the Ukrainian nationalists who assisted the [Wehrmacht] in killing the Jews. These people who ran newspapers with the most vile—that egged on Ukrainians to help with this [populicide]. […] It wasn’t enough to kill thirty‐three thousand people in two days. They, afterwards, they were running these […] newspapers saying, ‘Beware! There still may be Jews hiding in the city! Be vigilant for any survivors, lest there any who weren’t killed!’ Okay.

And these people—I mean, it just makes my blood boil—these people, you know, then listed them as victims, because eventually the [Axis] got tired of them and executed them too, these nationalists. And some people say [that] they were killed in Babi Yar, some people—there’s a lot of evidence that they weren’t actually killed in Babi Yar. But regardless of wherever they were killed, it would be like […] putting a memorial to the 9/11 hijackers at Ground Zero, ’cause technically they were killed there too. You know.

And the pain of it, and Jewish organizations stood there and they commemorated Babi Yar with this obscene, this obscene mockery, this perversion of a commemoration, and that’s just the tip of the iceberg, because Babi Yar does not have an actual museum complex, a comprehensive introduction: What is Babi Yar, what happened there, who killed who[m], who were the victims, who were the perpetrators.

(Mirror.)

On April 23, 1940 no more than two weeks after the [Fascist] invasion of Denmark and Norway, Himmler ordered the establishment of a Waffen SS unit which was to include volunteers from these two countries: The SS Standarte Nordland. The recruitment of Scandinavians to Nordland was designed to overcome the strict limits imposed on the growth of the Waffen SS by the Wehrmacht. The Wehrmacht had established a near‐monopoly on recruiting in Germany, forcing the Waffen SS to look outside Germany in its search for manpower.

In the end around 13,000 Danish citizens volunteered for [Fascist] armed service during the Second World War, some 7,000 of whom enlisted. The vast majority — around 12,000 — volunteered for the Waffen SS and the organization admitted around 6,000. The greater part of these Danes served in three different formations: Frikorps Danmark (The Danish Legion), SS Division Wiking and, after the disbandment of the so‐called legions in 1943, in SS Division Nordland. Approximately 1,500 Danish volunteers hailed from the German minority in southern Jutland and served mainly in the Division Totenkopf and to some extent in the 1st SS Brigade.

(Emphasis added, because nobody can excuse these anticommunists by saying that somebody ‘forced’ them to serve.)

Up until June 1941 recruitment did not make serious progress, but the [Axis] assault on the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941 made hitherto politically sceptical groups potential volunteers. The anticommunist theme now became dominant in recruitment propaganda designed to appeal to right‐wing nationalist groups who were not necessarily [Fascists].

Furthermore, physical requirements for volunteers diminished in subsequent years, as the engagement at the eastern front took a heavy toll in human lives. Right‐wing nationalist, but non‐Nazi groups were encouraged to enlist on the grounds that the war against the Soviet Union was a crusade to “protect Europe against Bolshevism”.

[…]

With 1,200 men Frikorps Danmark was sent to Demyansk south of Novgorod in May 1942. In less than three months the corps experienced the loss of close to 350 men who were either killed or wounded.^10^ After a one‐month refreshment and propaganda leave in Denmark the corps returned to the front in November 1941. Originally, Frikorps Danmark was supposed to join 1st SS Brigade in Byelorussia in its indiscriminate killing of civilians in areas associated with Soviet partisans.^11^

However, due to the deteriorating situation at the front both the 1st SS Brigade and the Frikorps were instead sent to frontline duty at the Russian town of Nevel, some 400 kilometers west of Moscow. In the spring of 1943 — as a consequence of further losses and inadequate reinforcements — the corps was down to 633 men and was withdrawn from the frontline.^12^

[…]

Naturally education of the rank and file was on a different level but incorporated nonetheless an endless number of ideological elements, from ordinary lectures in Weltanschauung to bayonet practice on Jewish‐looking cardboard figures.^26^ Correspondence also illustrates how several Danish volunteers identified with [Fascist] values.

But whereas it is easily shown how many Danish volunteers became radical anti‐Semites and otherwise ideologically inflamed, it is less easy to document the extent to which the Danish Waffen SS soldiers were involved in criminal actions against civilians and enemy POWs. Unfortunately, only a limited number of official documents related to the Waffen SS field units in question (such as war diaries and orders‐of‐the‐day) are available today. […] Nevertheless we can document a number of incidents.

During Frikorps Danmark’s first frontline engagement in the so‐called Demyansk pocket near Lake Illmen in northwest Russia, a trooper tells his diary that a [Soviet] POW was shot by a Danish Waffen SS volunteer, apparently because he stole cigarettes from the troops.^28^ The diary also mentions that a [Soviet] boy soldier around 12 was sentenced to death because he attempted to escape a prison camp.

Furthermore, evidence from different sources suggests that in a specific attack that included most of Frikorps Danmark a number of Russian POWs were shot in retaliation for the death of Frikorps commander von Schalburg. Von Schalburg was killed during the early phase of the assault and this apparently enraged the Danes. A Danish officer wrote home, “no prisoners were taken that day”.^29^

One especially brutal description, concerning the killing of a civilian Jew, also dates from the Demyansk period. It is one of the very few clear‐cut illustrations of how ideology and war crimes could be directly related. Thus another diary‐writing soldier notes the following:

A Jew in a greasy Kafkan walks up to beg some bread, a couple of comrades get a hold of him and drag him behind a building and a moment later he comes to an end. There isn’t any room for Jews in the new Europe, they’ve brought too much misery to the European people.^30^

After the disbandment of the Frikorps Danmark the men were transferred to the newly established Division Nordland and sent to Yugoslavia during the fall of 1943. Here they became involved in a very brutal fight with local partisans. On at least one occasion Danes from “Regiment Danmark” burned down an entire village from which shots had been fired, and despite finding no adult men there they apparently killed the inhabitants.^31^

The Danish officer Per Sørensen relates a story that might be addressing the same situation or perhaps one like it. In a letter that escaped censorship by travelling with a colleague to his parents, he brags about having killed 200 “reds” without suffering a single casualty.^32^

[…]

Another Dane, the doctor Carl Værnet, was among the doctors in [Axis] service who conducted medical experiments on inmates in the camps. During autumn 1944 in the Buchenwald concentration camp Værnet implanted an artificial “sexual gland” in 15 homosexual or effeminate male inmates in order “to cure them” from their “wrong” sexuality. The experiments were authorized by Himmler personally.

Though some of the prisoners submitted to Værnets “treatment” died, Værnet managed to avoid a post‐war trial, despite undergoing short internment and investigation by the Danish authorities.^39^

(Emphasis added in all cases. As always, the examples included in this excerpt were by no means the only ones from which to choose.)

Events that happened today (October 2):

1847: Paul von Hindenburg, conservative who helped promote the NSDAP to institutional power, was born.

1935: Benito Mussolini announced amid a large gathering of ministers, state secretaries and specially selected foreign dignitaries that war with Ethiopia was imminent.

1938: Alexandru Averescu, profascist Romanian, dropped dead.

1944: The Wehrmacht terminated the Warsaw Uprising.

Despite the just struggle of the Ethiopians for their liberation and the enormous support they enjoyed from Diaspora Africans and the worldwide condemnation of the fascist atrocities, however, the Allied Forces were insensitive to the Ethiopian cause at least till 1940 when Italy declared war on Britain. The British then were compelled to become objective allies of Ethiopia, but not necessarily genuine supporters of the Ethiopian cause.

In January 1942, the Allied leaders labeled Hitler’s government as ‘régime of terror’ and supported the idea of trying the Nazi war criminals while they were shy in condemning the fascist régime in Italy. In point of fact, both Hitler and Mussolini founded […] governments of the fascist type, shared [the] same ideology of jingoism, and were menace[s] to world peace and as such should have been treated equally. The difference between the two was that Hitler was a menace to the very existence of European nations while Mussolini was engaged in destroying a black nation and an island of independence in colonized Africa.

Adding fuel to the fire, long after Mussolini was ousted from power and Badoglio was appointed as prime minister by King Vittorio Emanuele, the Allied leaders, particularly the British, continued to ignore all charges of war crimes against Badoglio. By some secret machinations, Badoglio, who seemed to have promised the British to keep the peace and preserve stability in Italy, had become the ‘good guy’ in the eyes of the Allied Powers.

When the War Crimes Commission was established under the auspices of Britain on October 1943, Ethiopia was deliberately excluded from the Commission, due to fear, perhaps, that Ethiopians will demand the trial of the fascist criminals. In fact, Britain’s Foreign Office made all efforts to frustrate Ethiopian demands and the lobbying efforts of friends of Ethiopia and Sylvia Pankhurst in London. The efforts of Ethiopian officials in London, for instance that of Blatta Ayale Gebre during the formative period of the Commission and later in 1949 of Ato Abebe Retta was also frustrated.

For all intents and purposes, the British Foreign Office and the War Crimes Commission wanted to confine crime charges to the wars they were engaged in, i.e. beginning 1939 and not the 1935–36 Italo‐Ethiopian war. Ultimately, however, the Foreign Office reconsidered its position and decided to include the Ethiopian demand in June 1945 and subsequently invited allies to sign the London Agreement on August of the same year.

At long last, i.e. ten years after Emperor Haile Selassie appealed to the League, Ethiopia was in a position to establish the Ethiopian War Crimes Commission on May 1946 but it had encountered two major hurdles: 1) the Allied leaders were not willing to prosecute the [Fascist] war criminals; 2) Ethiopia did not have enough professional personnel who could gather data in regards to the fascist crimes and coherently present them before the War Crimes Commission.

One factor that contributed to the second deficiency was the systematic killings of the Ethiopian educated élite of the 1920s and 1930s. Thus, after Ethiopia established its own Commission, it took another eight months when Ato Ambaye Woldemariam submitted a report to the UN War Crimes Commission on behalf of Ethiopia.

[…]

Sometimes, history is indeed cruel. Marshall Badoglio, who ordered the use of poison gas against Ethiopians, without encountering any prosecution lived honorably and dignified, and in fact rewarded, till he died in 1956. Marshall Graziani, responsible for the 1937 massacres in Addis Ababa was tried by the Italian government in 1950, not for his crimes in Ethiopia but for his collaboration with the [Third Reich]. He served less than a year in prison although the pretentious and theatrical Italian court sentenced him to 19 years behind bars.

(Emphasis added.)

Events that happened today (October 1):

1878: Othmar Spann, Austrian protofascist, stained the earth.

1936: Francisco Franco was named head of Spain’s Nationalist government. (Coincidentally, the Central Committee of Antifascist Militias of Catalonia dissolved itself, handing control of Catalan defence militias over to the Generalitat.)