In a moment of distraction from the laborious work of marking an “enormous pile of examination papers”, J.R.R. Tolkien flipped to a blank page on a student essay and scribbled, “in a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit”.

This became the first line of The Hobbit (1937). From this doodle Tolkien went on to write one of the world’s most popular fantasy adventure series, The Lord of the Rings (1954).

His main work, however, was not as the writer of fantasies that made him so famous. For the 50th anniversary of Tolkien’s death, I want to celebrate Tolkien’s life as a medievalist and philologist (historian of languages), as well as some of his major contributions to the study of medieval literature.

Tolkein’s first teaching post was at the University of Leeds, where he worked on a translation of the 14th-century Middle English poem, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. For many, his is still one of the best translations.

Email Twitter Facebook3 LinkedIn Print

In a moment of distraction from the laborious work of marking an “enormous pile of examination papers”, J.R.R. Tolkien flipped to a blank page on a student essay and scribbled, “in a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit”.

This became the first line of The Hobbit (1937). From this doodle Tolkien went on to write one of the world’s most popular fantasy adventure series, The Lord of the Rings (1954).

His main work, however, was not as the writer of fantasies that made him so famous. For the 50th anniversary of Tolkien’s death, I want to celebrate Tolkien’s life as a medievalist and philologist (historian of languages), as well as some of his major contributions to the study of medieval literature.

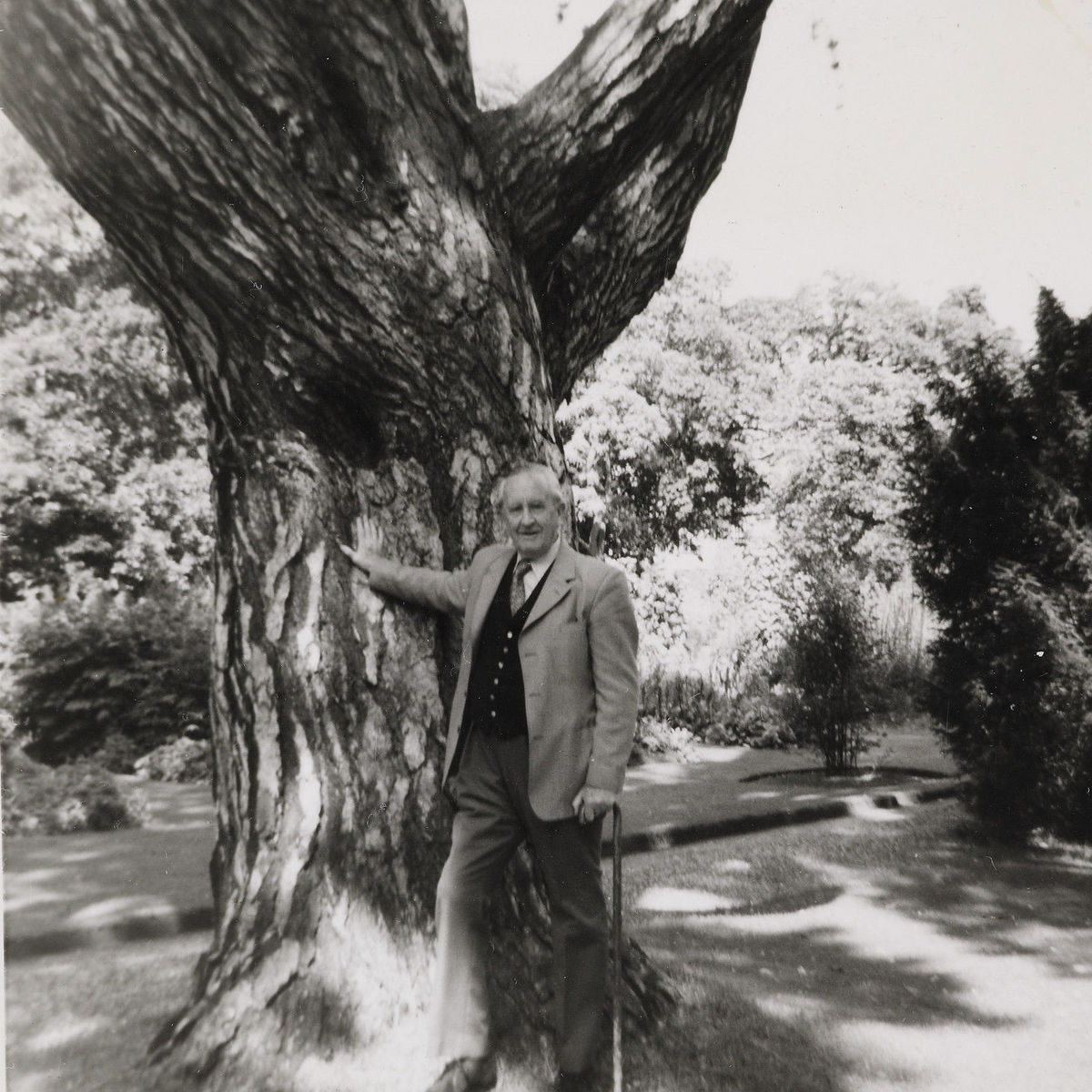

Tolkein’s first teaching post was at the University of Leeds, where he worked on a translation of the 14th-century Middle English poem, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. For many, his is still one of the best translations. Fight back against disinformation. Get your news here, direct from experts A black and white photograph of J.R.R. Tolkien. Photograph of J. R. R. Tolkien in the 1920s upon leaving Leeds University. Bodleian Library

In 1925, Tolkien won a professorship at the University of Oxford. A year later he translated the Old English poem, Beowulf. He remained a professor of English language and literature for the next 20 years.

Tolkien’s world was in a state of flux. The rudderless turmoil of the two world wars undoubtedly had affected his writing and this is possibly why his preference for settings was always for pre-industrial England. This can be seen in his love of fairy tales and in his drawings, which are almost all natural landscapes, with little architecture.

His love of trees was so great that he wrote a letter to his publisher saying: “I am (obviously) much in love with plants and above all trees, and always have been and I find human mistreatment of them as hard to bear as some find ill-treatment of animals.” In another, he talks of his fondness for myth, fairy tales “and above all for heroic legend”.

A mythology for England

Tolkien’s biographer, Humphrey Carpenter, argues that he was attempting to create “a mythology for England” through his fantasy fiction, by creating an imaginary world with its own languages, history, cultures and people.

Tolkien did this by drawing not only on his knowledge of languages and literature in Old and Middle English, but also on those languages that influenced the cultural and historical development of Britain, such as Finnish, Welsh, Old Norse, Old High and Middle German.

He loved languages – both ancient and modern – and was well versed in more than a few, including Finnish, Welsh, Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Danish, Old Norse, Old English and Old Icelandic, as well as his invented Elvish languages Quenya and Sindarin, which have full etymologies.

Tolkien wrote in a letter in 1951 about his desire to “make a body of more or less connected legend, ranging from the large and cosmogonic to the level of romantic fairy-story”. He wanted to dedicate it “simply: to England: to my country”.

The source of inspiration for this “mythology for England” was the medieval world Tolkien knew so well from his scholarly studies.

‘Northern courage’

One theme that Tolkien picked up from his work in medieval literature – and which runs like a thread throughout his fictional worlds – is the reckless bravery and heroic courage that many medieval protagonists exhibit.

Tolkien termed this kind of response to challenge “northern courage” in his 1936 essay, Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics. It was “northern” because this type of courage is highly prevalent in the Old Norse sagas that Tolkien was so familiar with and which grew out of the northern Scandinavian countries between the 9th and 13th centuries. This concept is probably best expressed in a line from the Old English poem, The Battle of Maldon (AD991): “Will shall be the sterner, heart the bolder, spirit the greater as our strength lessens.”

Simply put, northern courage is when one exhibits the courage to keep persevering despite the knowledge that sooner or later defeat is inevitable. In constructing his “mythology for England”, Tolkien drew on medieval poems such as Beowulf and The Battle of Maldon as he argued that the people of ancient England would have had a “fundamentally similar heroic temper”.

Email Twitter Facebook3 LinkedIn Print

In a moment of distraction from the laborious work of marking an “enormous pile of examination papers”, J.R.R. Tolkien flipped to a blank page on a student essay and scribbled, “in a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit”.

This became the first line of The Hobbit (1937). From this doodle Tolkien went on to write one of the world’s most popular fantasy adventure series, The Lord of the Rings (1954).

His main work, however, was not as the writer of fantasies that made him so famous. For the 50th anniversary of Tolkien’s death, I want to celebrate Tolkien’s life as a medievalist and philologist (historian of languages), as well as some of his major contributions to the study of medieval literature.

Tolkein’s first teaching post was at the University of Leeds, where he worked on a translation of the 14th-century Middle English poem, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. For many, his is still one of the best translations. Fight back against disinformation. Get your news here, direct from experts A black and white photograph of J.R.R. Tolkien. Photograph of J. R. R. Tolkien in the 1920s upon leaving Leeds University. Bodleian Library

In 1925, Tolkien won a professorship at the University of Oxford. A year later he translated the Old English poem, Beowulf. He remained a professor of English language and literature for the next 20 years.

Tolkien’s world was in a state of flux. The rudderless turmoil of the two world wars undoubtedly had affected his writing and this is possibly why his preference for settings was always for pre-industrial England. This can be seen in his love of fairy tales and in his drawings, which are almost all natural landscapes, with little architecture.

His love of trees was so great that he wrote a letter to his publisher saying: “I am (obviously) much in love with plants and above all trees, and always have been and I find human mistreatment of them as hard to bear as some find ill-treatment of animals.” In another, he talks of his fondness for myth, fairy tales “and above all for heroic legend”. A mythology for England

Tolkien’s biographer, Humphrey Carpenter, argues that he was attempting to create “a mythology for England” through his fantasy fiction, by creating an imaginary world with its own languages, history, cultures and people.

Tolkien did this by drawing not only on his knowledge of languages and literature in Old and Middle English, but also on those languages that influenced the cultural and historical development of Britain, such as Finnish, Welsh, Old Norse, Old High and Middle German. Four knights battling in front of a castle. An illustration of knights from a Medieval manuscript. British Library, CC BY-SA

He loved languages – both ancient and modern – and was well versed in more than a few, including Finnish, Welsh, Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Danish, Old Norse, Old English and Old Icelandic, as well as his invented Elvish languages Quenya and Sindarin, which have full etymologies.

Tolkien wrote in a letter in 1951 about his desire to “make a body of more or less connected legend, ranging from the large and cosmogonic to the level of romantic fairy-story”. He wanted to dedicate it “simply: to England: to my country”.

The source of inspiration for this “mythology for England” was the medieval world Tolkien knew so well from his scholarly studies. ‘Northern courage’

One theme that Tolkien picked up from his work in medieval literature – and which runs like a thread throughout his fictional worlds – is the reckless bravery and heroic courage that many medieval protagonists exhibit.

Tolkien termed this kind of response to challenge “northern courage” in his 1936 essay, Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics. It was “northern” because this type of courage is highly prevalent in the Old Norse sagas that Tolkien was so familiar with and which grew out of the northern Scandinavian countries between the 9th and 13th centuries. This concept is probably best expressed in a line from the Old English poem, The Battle of Maldon (AD991): “Will shall be the sterner, heart the bolder, spirit the greater as our strength lessens.”

Simply put, northern courage is when one exhibits the courage to keep persevering despite the knowledge that sooner or later defeat is inevitable. In constructing his “mythology for England”, Tolkien drew on medieval poems such as Beowulf and The Battle of Maldon as he argued that the people of ancient England would have had a “fundamentally similar heroic temper”.

Northern courage in Lord of the Rings

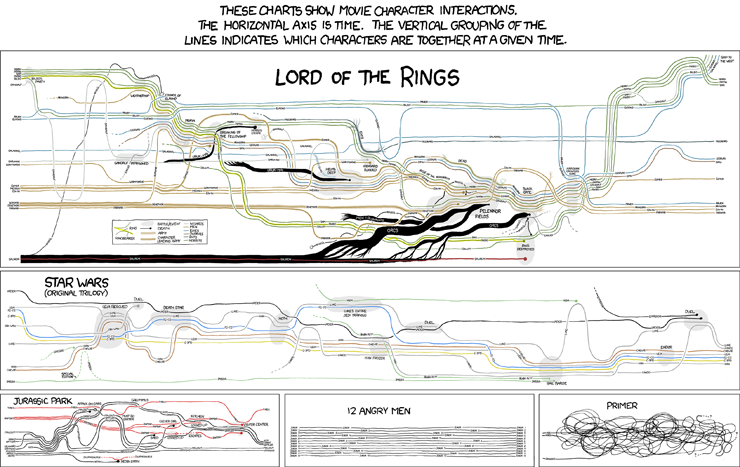

Northern courage is at work in The Lord of the Rings, when Gandalf confronts the Balrog on the bridge of Khazad-Dûm. In blocking the Balrog – and shouting his famous line, “you shall not pass” – he refuses to allow the enemy to cross the bridge and buys time for the rest of the fellowship to escape. He exhibits magnanimous courage and perseverance in the face of inevitable defeat.

In a different way, the protagonists Bilbo and Frodo Baggins exhibit courage as they leave the comforts of the Shire to fulfil a greater heroic duty. This is probably best summed up in Frodo’s exchange with Gandalf:

“I wish it need not have happened in my time”, said Frodo. “So do I,” said Gandalf, “and so do all who live to see such times. But that is not for them to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.”

The wizard’s words here are steeped in northern courage. They insist that we must rise to the challenges offered in our time.

Fifty years on from Tokien’s death, that spirit of northern bravery endures as an alluring concept. What makes Tolkien’s fantastical world so appealing is the recurrent suggestion that the courage manifested to defeat the big monsters in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings is the very same courage that can be found in hopeless situations of a more ordinary sort.

Author: Madeleine S. Killacky, PhD Candidate, Medieval Literature, Bangor University

*

* extract

extract